Workshop Tower, Los Angeles, CA, USA:

Further information and case study for this project can be found at the De Gruyter Birkhäuser Modern Construction Online database

The following architectural theory-based case study is not available at Modern Construction Online

Architectural Design of the Workshop Tower — Programmatic Stratification and Vertical Integration

Introduction

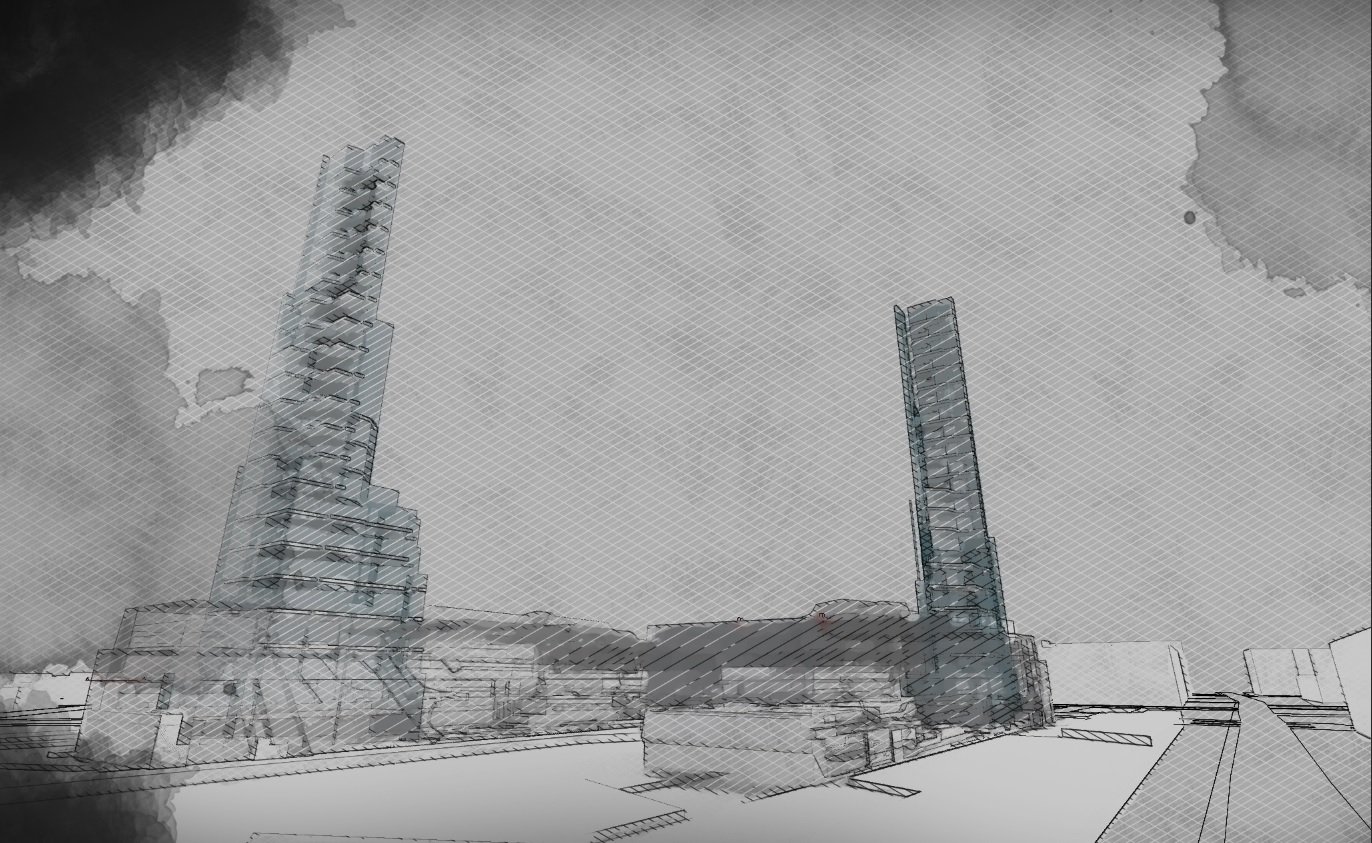

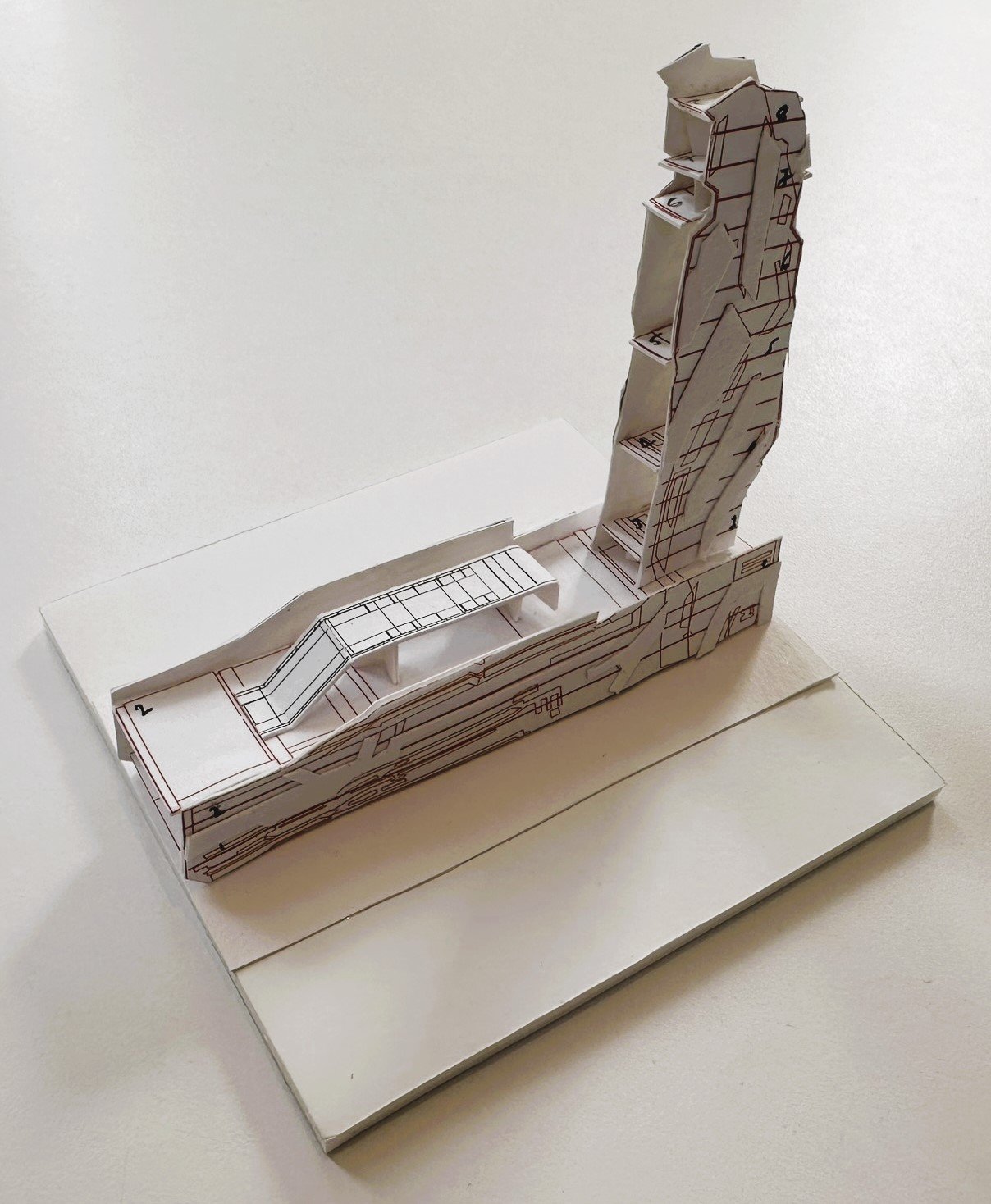

The Workshop Tower employs a podium-and-tower typology rooted in modernist urbanism, facilitating a functional separation between public and private zones while promoting vertical intensification of land use (Hilberseimer, 1944). The podium accommodates expansive ground-level industrial workshops, whereas the tower stacks creative studios vertically above. This programmatic stratification enables a diverse range of operations—from vehicle prototyping in the base to product design and innovation in the upper levels—while maintaining spatial coherence across volumes.

Designed by Newtecnic, who served as both architect and interdisciplinary engineer, the project exemplifies an integrated approach that underpins its technological ambitions. The façade acts not only as a climatic and spatial interface but also as a structural and infrastructural system, corresponding closely with the performative envelope strategies articulated in Modern Construction Envelopes (Watts, 2019).

Precedent-Informed Design Strategy from Modern Structural Design

Project 03’s design was shaped by principles derived from Project 10 in Modern Structural Design, particularly its use of a mixed structural system combining reinforced concrete and steel to meet varying structural demands without redundant secondary elements. This strategy informed Project 03’s embedding of balconies, projecting floor plates, and service runs within the primary structure, enabling efficient spatial use and minimizing material duplication. Similar to Project 10, GFRC cladding was selected to provide both environmental protection and a unifying visual language that complements the exposed concrete interiors.

The spatial configuration—balancing compactness and openness—draws on the mini-tower and podium concept to maximize daylight penetration and programmatic differentiation within a dense urban context. Services are housed in vertical modules attached to shear walls, while passive shading is integrated into the façade, achieving flexibility and high performance that support diverse uses while maintaining structural and acoustic integrity.

Historical High Modernist Parallels

The Workshop Tower draws conceptual and formal inspiration from seminal High Modernist precedents that pioneered programmatic stratification and vertical integration. James Stirling’s Leicester Engineering Building (1963) famously articulates distinct industrial functions through clear structural expression and spatial layering—a comparison explored further in a separate case study.

Likewise, Le Corbusier’s Unité d'Habitation (1952) introduced modular vertical living combined with communal infrastructure, championing programmatic diversity within a singular volumetric entity. This approach resonates with the Workshop Tower’s vision of vertically stratified yet interconnected zones supporting varied activities.

The Seagram Building (1958) by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe and Philip Johnson exemplifies the modernist ideal of transparent façades paired with rigid structural logic, expressing infrastructural clarity that parallels the Workshop Tower’s façade system, where the envelope serves as both load-bearing structure and environmental mediator.

Walter Gropius’s Bauhaus Dessau (1925–26) also provides an early precedent for integrating production, administration, and education within one complex, setting a standard for hybrid programmatic architectures transcending conventional zoning. This principle is echoed in the Workshop Tower’s co-location of industrial fabrication and creative studio spaces.

Application of Façade Technology from the Moscow Tower

The façade technology developed for the Moscow Tower, as detailed in Modern Construction Case Studies (Watts, 2016), directly influenced the Workshop Tower’s envelope design and delivery. In both projects, the façade operates as a multifunctional, load-sharing system synthesizing structural, environmental, and spatial performance. The Moscow Tower’s parametrically generated exoskeletal framework—featuring CNC-fabricated steel node connectors and aluminium support members—provided a key technological precedent.

For the Workshop Tower, this approach was adapted to accommodate a vertically stratified, hybrid program requiring enhanced modular flexibility and decentralized service integration. The coupling of structural and environmental logic within a single tectonic system was central to this transfer of technology.

Real-time parametric workflows employed in the Moscow Tower, using tools such as Karamba3D and Grasshopper, were extended to the Workshop Tower to align geometry, structural behaviour, and solar performance. Specific detailing innovations—such as slip-joint brackets that absorb wind loads and thermal movement without compromising fabrication tolerances—were directly inspired by Moscow Tower solutions.

Moreover, the Moscow Tower’s concept of the envelope as an infrastructural scaffold capable of supporting externalized MEP systems, solar shading, and vertical access informed the Workshop Tower’s rejection of the central-core typology. Instead, prefabricated service spines were installed along the structural perimeter, enabling phased installation, tenant-specific upgrades, and lifecycle adaptability. This integrated envelope strategy reflects Watts’s (2016) performative façade principles, positioning the envelope as a programmable interface bridging structure, services, and inhabitation.

Programmatic Duality and Hybrid Functionality

The Workshop Tower reinterprets functional zoning by introducing a hybrid live–work–production model. Heavy industrial fabrication takes place in the podium, while flexible creative workspaces occupy the tower above. This co-location fosters iterative design, prototyping, and manufacturing processes within a unified architectural framework.

This programmatic hybridization aligns with strategies described in Modern Construction Case Studies (Watts, 2019), which advocate layered programming to enhance operational efficiency and collaborative engagement within vertically organized buildings.

Vertical Spatial Organisation and Connectivity

The tower’s layout consists of stacked three-storey units linked by bridging galleries, creating vertical “neighbourhoods” that form micro-communities both visually and spatially interconnected. Inspired by Kurokawa’s (1977) modular concepts, this system encourages collective identity and informal interaction across multiple levels.

The internal bridges also serve as architectural devices, articulating circulation externally while framing internal views. This strategy rejects the generic repetition typical of commercial towers, favouring a more articulated and socially responsive spatial experience. It echoes tectonic principles explored in Modern Construction Handbook (Watts, 2023), where vertical organisation promotes legibility and flexibility.

Environmental Systems and Infrastructural Decentralisation

Breaking from the central-core typology, the building externalizes all major MEP systems. Prefabricated service spines affixed to the structural perimeter with modular, reversible connections allow for phased installation and tenant-specific adaptations with minimal disruption.

Parametric tools such as Grasshopper and Revit-Dynamo were used to align these systems precisely with the building’s geometry in real time. This integrated infrastructure approach reflects methodologies outlined in Modern Environmental Design (Watts, 2022), emphasizing coordinated service planning to enable lifecycle adaptability and superior environmental performance.

Tectonics, Façade, and Spatial Legibility

The façade is conceived as a load-sharing, parametrically derived system composed of CNC-fabricated components. Aluminium subframes, laser-cut steel node connectors, and slip-joint brackets accommodate fabrication tolerances and in-service movements caused by wind and thermal expansion. Karamba3D simulations refined the geometry to optimize solar shading and structural stress distribution.

This method produces a “thickened skin”—a layered, multifunctional surface integrating shading, load transfer, environmental control, and visual depth. It embodies principles of mass customization (Kolarevic, 2003), where digital fabrication enables technically resolved yet expressive architectural envelopes.

As Watts (2019) asserts in Modern Construction Envelopes, the façade transcends a mere barrier to become an infrastructural and spatial framework enhancing legibility, performance, and adaptability. Its integration of structural function also aligns with themes in Modern Structural Design (Watts, 2022), where façades actively participate in load transfer and spatial clarity.

Conclusion

The Workshop Tower exemplifies a contemporary evolution of the vertical industrial typology. Designed by Newtecnic as both architect and interdisciplinary engineer, the project integrates programmatic diversity, spatial connectivity, and environmental performance through a highly articulated façade system.

The building envelope functions as an active, performative scaffold—a concept central to Watts’s body of work (2019, 2022, 2023)—bridging structure, services, and occupation. This approach provides a framework for adaptable inhabitation and future transformation, positioning the façade as both a technological and cultural interface.

References

Banham, R. (1986) A Concrete Atlantis: U.S. Industrial Building and European Modern Architecture 1900–1925. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Eastman, C., Teicholz, P., Sacks, R. and Liston, K. (2011) BIM Handbook: A Guide to Building Information Modeling for Owners, Managers, Designers, Engineers and Contractors. 2nd edn. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Frampton, K. (1995) Studies in Tectonic Culture: The Poetics of Construction in Nineteenth and Twentieth Century Architecture. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Gramazio, F. and Kohler, M. (2008) Digital Materiality in Architecture. Basel: Birkhäuser.

Hilberseimer, L. (1944) The New City: Principles of Planning. Chicago: Paul Theobald.

Kolarevic, B. (2003) Architecture in the Digital Age: Design and Manufacturing. New York: Taylor & Francis.

Kurokawa, K. (1977) Metabolism in Architecture. London: Studio Vista.

Le Corbusier (1952) Unité d'Habitation. Marseille, France.

Mies van der Rohe, L. and Johnson, P. (1958) Seagram Building. New York, NY, USA.

Preisinger, C. (2013) ‘Linking structure and parametric geometry’, Architectural Design, 83(2), pp. 110–113.

Smithson, A. and Smithson, P. (1965) ‘The charged void: urbanism’, Architectural Design, 35(9), pp. 414–421.

Stirling, J. (1963) Leicester Engineering Building. Leicester, UK.

Watts, A. (2016) Modern Construction Case Studies. 1st ed. Basel: Birkhäuser.

Watts, A. (2019) Modern Construction Case Studies. 2nd ed. Basel: Birkhäuser.

Watts, A. (2019) Modern Construction Envelopes. 3rd ed. Basel: Birkhäuser.

Watts, A. (2022) Modern Environmental Design. Basel: Birkhäuser.

Watts, A. (2022) Modern Structural Design. Basel: Birkhäuser.

Watts, A. (2023) Modern Construction Handbook. 6th ed. Basel: Birkhäuser.