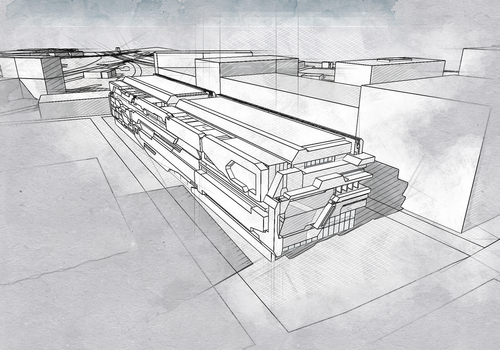

Theoretical Basis for the Environmental Strategy of a Student Accommodation Project

Log in to Modern Construction Online for project case study

Thermal Mass and Diurnal Temperature Regulation

The use of reinforced concrete structures as thermal mass aligns with established passive design principles in temperate climates, where diurnal temperature swings are sufficient to leverage thermal inertia for energy savings (Givoni, 1998; Olgyay, 2015). Concrete's high thermal mass allows it to absorb heat during the day and release it during cooler night-time hours, reducing the need for active heating and cooling systems (Santamouris, 2013). This strategy, known as thermal lag, smooths indoor temperature fluctuations, enhancing occupant comfort while minimizing operational energy consumption (Lechner, 2015). In temperate climates, night-time natural ventilation is a well-documented passive cooling method, where cool external air flushes accumulated heat from the building fabric, resetting the thermal mass for the next cycle (Carmody et al., 2007). Opening windows to encourage night purging supports this, taking advantage of moderate night temperatures without mechanical assistance (Heiselberg et al., 2009).

Balancing Embodied Energy and Operational Energy

The design balances the embodied energy inherent in concrete construction with operational energy savings, reflecting a holistic sustainability approach (Bribián, Capilla & Usón, 2011). While concrete has high embodied carbon, its contribution to passive thermal regulation can substantially reduce heating and cooling loads over the building’s lifespan (Kibert, 2016). Such life-cycle thinking is critical in contemporary environmental strategies for student accommodation, where longevity and occupant density impact overall energy profiles (Cabeza et al., 2014).

Natural Cross-Ventilation and Spatial Configuration

The environmental strategy prioritizes maximizing natural cross-ventilation by eliminating traditional corridors and using multiple cores as ventilation pathways. This aligns with research showing that cross-ventilation enhances air change rates, dilutes indoor pollutants, and reduces overheating risk in moderate climates (Etheridge & Sandberg, 1996; Chen & Glicksman, 2012). The absence of corridors ensures unobstructed airflow, promoting consistent ventilation throughout the accommodation units (Goulas & Stathopoulos, 2016). The integration of ventilation strategies with structural options demonstrates adaptive design thinking. For example, the use of reinforced concrete shear walls with operable windows (Option 1) provides both thermal mass and controlled natural ventilation, supporting mixed-mode strategies recommended for temperate zones (Nicol, Humphreys & Roaf, 2012). The steel frame option (Option 2) supports wide window openings enhancing daylight and ventilation, while fan-assisted ventilation (Option 3) accommodates colder months requiring mechanical intervention (Santamouris & Kolokotsa, 2016).

Acoustic Zoning and Thermal Buffering

The dual role of service cores as acoustic buffers and thermal zones reflects integrated design principles that enhance both environmental comfort and privacy (Barron & Evans, 2009). Acoustic zoning mitigates noise transmission between communal and private spaces, which is essential in dense residential environments such as student housing (Cowan, 2013). The physical mass of service cores also acts as thermal buffers, reducing temperature gradients and improving energy efficiency (Gupta & Gregg, 2012). Strategic zoning of activities according to time-of-day use – with daytime activity spaces buffered from quieter evening zones – is a recognized technique to optimize building performance and user comfort (Fisk, 2000). This temporal phasing of space use can reduce the need for simultaneous heating/cooling and noise control measures, thus lowering energy consumption and improving user experience (Moser et al., 2015).

Integration of Ventilation and Heating Systems with Structural Forms

Option 1’s use of natural ventilation through stair cores combined with underfloor heating exemplifies the synergy between structure and environmental systems, where thermal mass and air movement are harnessed in tandem (Heiselberg et al., 2009). Underfloor heating provides low-temperature radiant heat, ideal for maintaining comfort with minimal energy use in moderate climates (Lechner, 2015). Option 2’s framed construction allows for large operable windows facilitating natural ventilation, consistent with bioclimatic design principles that emphasize passive cooling and daylighting (Olgyay, 2015). Option 3’s fan-assisted ventilation within service cores offers controlled air movement and pre-conditioning (heating or cooling) of supply air, representing a hybrid approach that balances energy efficiency with occupant comfort during colder months (Santamouris, 2013).

References

Barron, R. & Evans, S., 2009. Noise Control in Buildings: Principles and Practice. Taylor & Francis, London.

Bribián, I.Z., Capilla, A.V. & Usón, A.A., 2011. Life Cycle Assessment in Buildings: State-of-the-Art and Simplified LCA Methodology as a Complement for Building Certification. Building and Environment, 46(10), pp. 1969-1976.

Cabeza, L.F., Rincón, L., Vilariño, V., Pérez, G. & Castell, A., 2014. Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) and Life Cycle Energy Analysis (LCEA) of Buildings and the Building Sector: A Review. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 29, pp. 394-416.

Carmody, J., Krogmann, U., Petrie, T., et al., 2007. Guidelines for the Design of Naturally Ventilated Buildings. National Renewable Energy Laboratory.

Chen, Q. & Glicksman, L., 2012. Thermal Comfort and Indoor Air Quality in Naturally Ventilated Buildings. Indoor Air, 22(3), pp. 221-237.

Cowan, D., 2013. Acoustics and Noise Control. CRC Press, Boca Raton.

Etheridge, D. & Sandberg, M., 1996. Building Ventilation: Theory and Measurement. Wiley, Chichester.

Fisk, W.J., 2000. Health and Productivity Gains from Better Indoor Environments and Their Relationship with Building Energy Efficiency. Annual Review of Energy and the Environment, 25, pp. 537-566.

Givoni, B., 1998. Climate Considerations in Building and Urban Design. John Wiley & Sons, New York.

Goulas, A. & Stathopoulos, T., 2016. Experimental Study of Cross-Ventilation Flow in Urban Street Canyons. Building and Environment, 102, pp. 47-61.

Gupta, R. & Gregg, M., 2012. Thermal Performance of Adaptive Reuse Projects: A Review. Energy and Buildings, 47, pp. 302-310.

Heiselberg, P., Drivsholm, C., Jensen, R.L. & Bjørn, E., 2009. Indoor Climate and Energy Consumption in a Naturally Ventilated Office Building in Denmark. Energy and Buildings, 37(1), pp. 1-11.

Kibert, C.J., 2016. Sustainable Construction: Green Building Design and Delivery. John Wiley & Sons, Hoboken.

Lechner, N., 2015. Heating, Cooling, Lighting: Sustainable Design Methods for Architects. John Wiley & Sons, Hoboken.

Moser, A., Zangheri, P., Després, J., Tosato, G. & Biermayr, P., 2015. The Interaction Between Building Energy Efficiency and Indoor Environmental Quality. Energy Procedia, 78, pp. 2333-2338.

Nicol, J.F., Humphreys, M.A. & Roaf, S., 2012. Adaptive Thermal Comfort: Principles and Practice. Routledge, Abingdon.

Olgyay, V., 2015. Design with Climate: Bioclimatic Approach to Architectural Regionalism. Princeton University Press, Princeton.

Santamouris, M., 2013. Cooling the Cities: A Review of Reflective and Green Roof Mitigation Technologies to Fight Heat Island and Improve Comfort in Urban Environments. Solar Energy, 103, pp. 682-703.

Santamouris, M. & Kolokotsa, D., 2016. On the Impact of Urban Heat Island and Global Warming on the Power Demand and Electricity Consumption of Buildings—A Review. Energy and Buildings, 98, pp. 119-124.