Theoretical Basis of an Environmental Strategy for a University Science Teaching Building

Log in to Modern Construction Online for project case study

Integration of Natural Ventilation and Daylighting

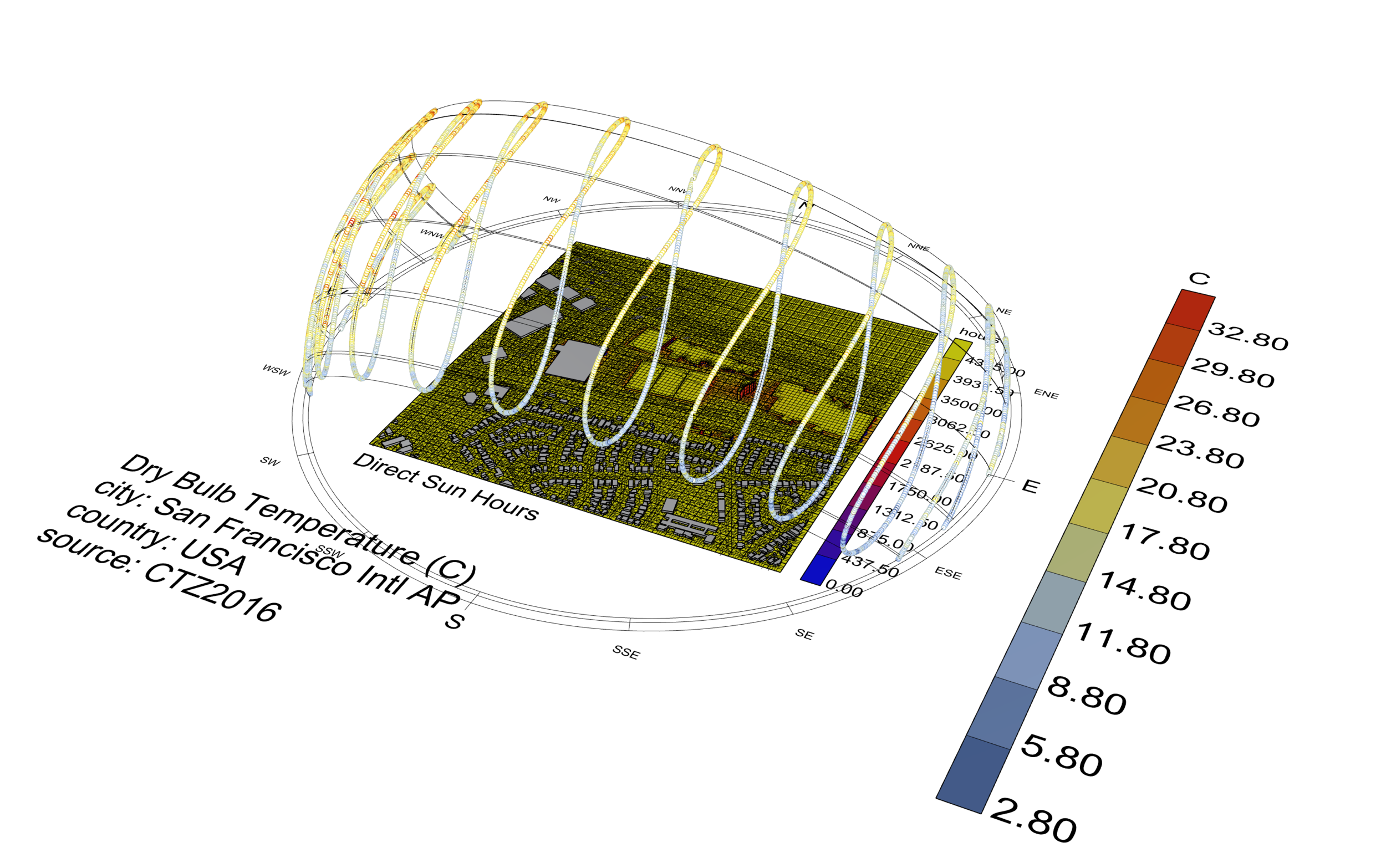

The environmental strategy prioritizes the integration of natural ventilation and daylighting—two key sustainable design principles that enhance occupant comfort, reduce energy consumption, and improve indoor environmental quality (IEQ) (Santamouris, 2013; CIBSE, 2021). The deliberate formation of architectural “crevices” and openings deep within the building plan reflects an understanding of how building geometry influences airflow and daylight penetration (Lechner, 2015). By avoiding a conventional narrow glass-box design typical of office buildings, the design balances the competing demands of site compactness and environmental performance. This approach aligns with research that demonstrates the importance of volumetric separation to maximize daylight penetration between building blocks while maintaining a compact site footprint (Dubois and Blomsterberg, 2006; Boubekri, 2008). The use of long “slot”-style windows supports controlled daylight admission to teaching spaces, reducing reliance on artificial lighting while minimizing glare and solar heat gain (Veitch and Newsham, 2000).

Zoning for Cross Ventilation and Mechanical Support

The strategy’s division of the building into separate environmental zones for activity or main spaces enables effective cross ventilation, a crucial design feature in temperate climates where moderate outdoor temperatures can be exploited for cooling and air quality (Awbi, 2013). This approach facilitates occupant control over ventilation, supporting both natural and mechanical systems—a hybrid ventilation strategy shown to improve energy efficiency and IEQ (Rupp et al., 2015; Leaman and Bordass, 2007). The use of operable windows and ventilation panels across a large facade area, as opposed to small trickle ventilators, improves airflow rates and user comfort (Schiavon and Zecchin, 2015). Electrically-operated fans integrated into the mechanical ventilation system provide supplementary airflow during periods when natural ventilation alone is insufficient, enabling seasonal flexibility without excessive energy use (ASHRAE, 2019).

Environmental Zoning and Daylight Distribution

The environmental zoning strategy for Options 1, 2, and 3 reflects a nuanced response to daylight distribution and solar exposure, consistent with established principles of daylighting and thermal comfort design (Kolarevic, 2003). Zones with different daylight qualities—such as end spaces with triple-aspect glazing versus centrally daylit spaces—allow tailored shading and mechanical control systems, enhancing occupant comfort and energy performance (Nabil and Mardaljevic, 2005). The segmentation into distinct environmental zones also facilitates solar control strategies, especially on east- and west-facing facades where solar heat gain can be problematic (Givoni, 1998). Integrating shading devices and managing facade exposure reduce cooling loads while maintaining visual comfort (Baker and Steemers, 2000).

Structural and Environmental Grid Coordination

The alignment of the building’s structural grid with the environmental grid, including ducts and task lighting, exemplifies integrated design—a core tenet of sustainable architecture (Kibert, 2016). This coordinated approach minimizes conflicts between architectural, structural, and mechanical systems, optimizing both spatial efficiency and environmental performance (Preiser and Vischer, 2005). Using ceiling-level ducts for both mechanical ventilation and lighting supports flexible control and future adaptability. Furthermore, natural ventilation operates along these same grids, promoting consistent airflow patterns. This system, which incorporates mechanical extraction and supply alongside operable windows, aligns with findings that hybrid ventilation systems are optimal in climates with significant seasonal variation (Hens, 2012).

Bridges as Environmental Zones

The conceptualization of bridges as distinct environmental zones further expands the environmental strategy by considering solar gain, shading, and thermal insulation (Ochoa and Capeluto, 2009). Opaque, thermally insulated roofs with overhangs provide passive solar shading for rooflights, reducing cooling loads while admitting diffused daylight. This approach draws on passive solar design principles that optimize building envelope performance and occupant comfort (Olgyay, 1963; Lechner, 2015). The placement and configuration of bridges influence microclimate conditions, offering opportunities for daylight harvesting, natural ventilation pathways, and thermal buffers between blocks, all contributing to the building’s overall environmental performance (Grobman et al., 2014).

References

ASHRAE, 2019. ASHRAE Handbook: HVAC Applications. Atlanta: ASHRAE.

Awbi, H.B., 2013. Ventilation of Buildings. 2nd ed. Abingdon: Routledge.

Baker, N. and Steemers, K., 2000. Energy and Environment in Architecture: A Technical Design Guide. London: E & FN Spon.

Boubekri, M., 2008. Daylighting, Architecture and Health: Building Design Strategies. New York: Routledge.

CIBSE, 2021. Guide A: Environmental Design. London: Chartered Institution of Building Services Engineers.

Dubois, M.C. and Blomsterberg, Å., 2006. Impact of occupancy and building operation on energy use and comfort. Energy and Buildings, 38(7), pp. 834-840.

Givoni, B., 1998. Climate Considerations in Building and Urban Design. New York: Wiley.

Grobman, Y.J., Masson, S. and Selkowitz, S.E., 2014. The role of design details in passive solar buildings. Energy and Buildings, 84, pp. 44-54.

Hens, H., 2012. Passive and Low Energy Cooling of Buildings. 3rd ed. London: Routledge.

Kibert, C.J., 2016. Sustainable Construction: Green Building Design and Delivery. 4th ed. Hoboken: Wiley.

Kolarevic, B., 2003. Architecture in the Digital Age: Design and Manufacturing. New York: Spon Press.

Lechner, N., 2015. Heating, Cooling, Lighting: Sustainable Design Methods for Architects. 4th ed. Hoboken: Wiley.

Nabil, A. and Mardaljevic, J., 2005. Useful daylight illuminances: A replacement for daylight factors. Energy and Buildings, 38(7), pp. 905-913.

Ochoa, C.E. and Capeluto, I.G., 2009. The effect of shading devices on building energy consumption. Energy and Buildings, 41(3), pp. 223-231.

Olgyay, V., 1963. Design with Climate: Bioclimatic Approach to Architectural Regionalism. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Preiser, W.F.E. and Vischer, J.C., 2005. Assessing Building Performance. Oxford: Elsevier.

Rupp, R.F., et al., 2015. Hybrid ventilation systems in office buildings: A review. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 41, pp. 133-141.

Santamouris, M., 2013. Energy and Climate in the Urban Built Environment. London: Routledge.

Schiavon, S. and Zecchin, R., 2015. Natural ventilation performance in office buildings. Building and Environment, 93, pp. 89-98.

Veitch, J.A. and Newsham, G.R., 2000. Preferred luminous conditions in open-plan offices: Research and practice recommendations. Lighting Research & Technology, 32(4), pp. 199-212.