Theoretical Basis of an Environmental Strategy for a Factory Building

Log in to Modern Construction Online for project case study

Zoning and Environmental Control

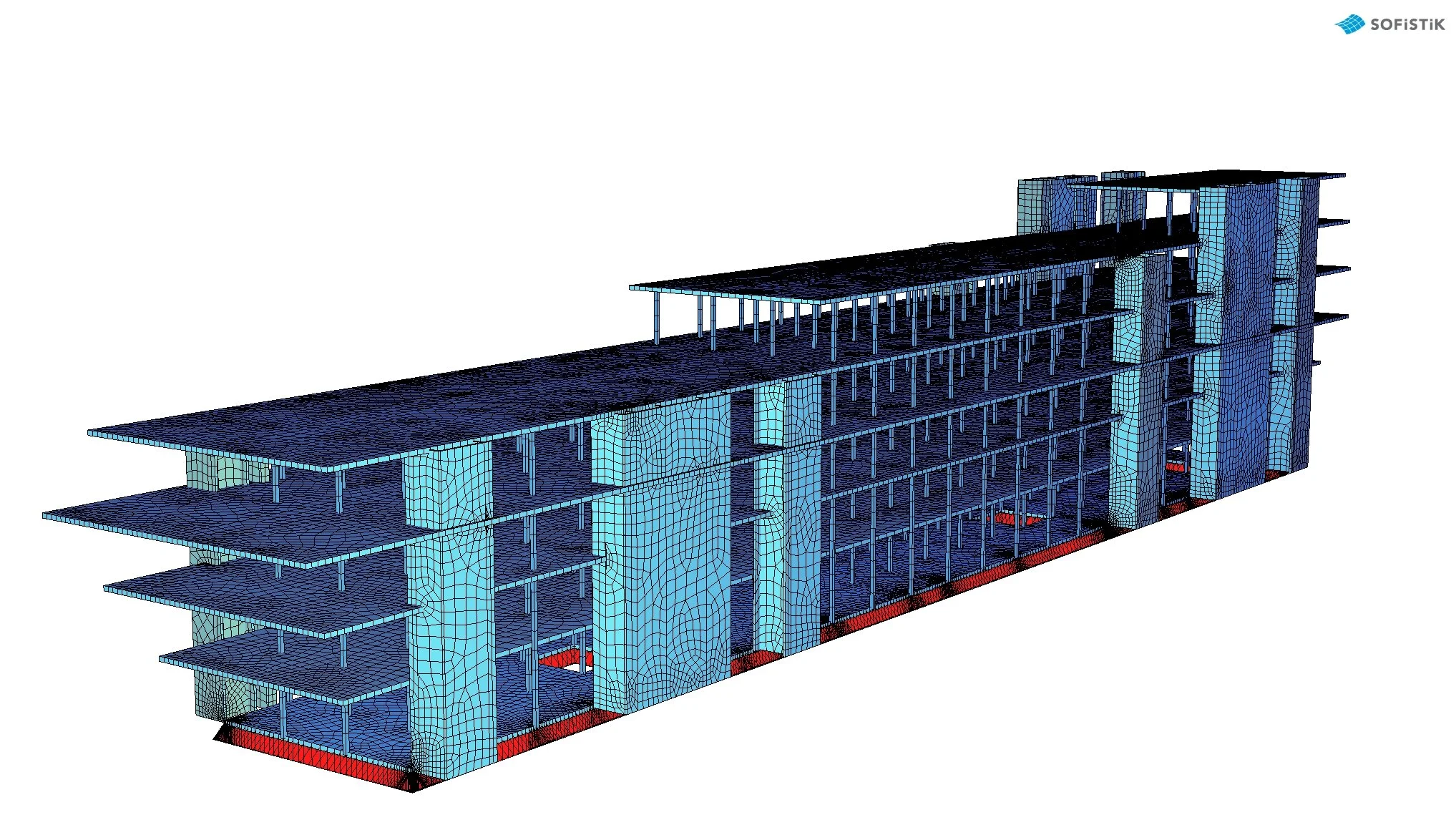

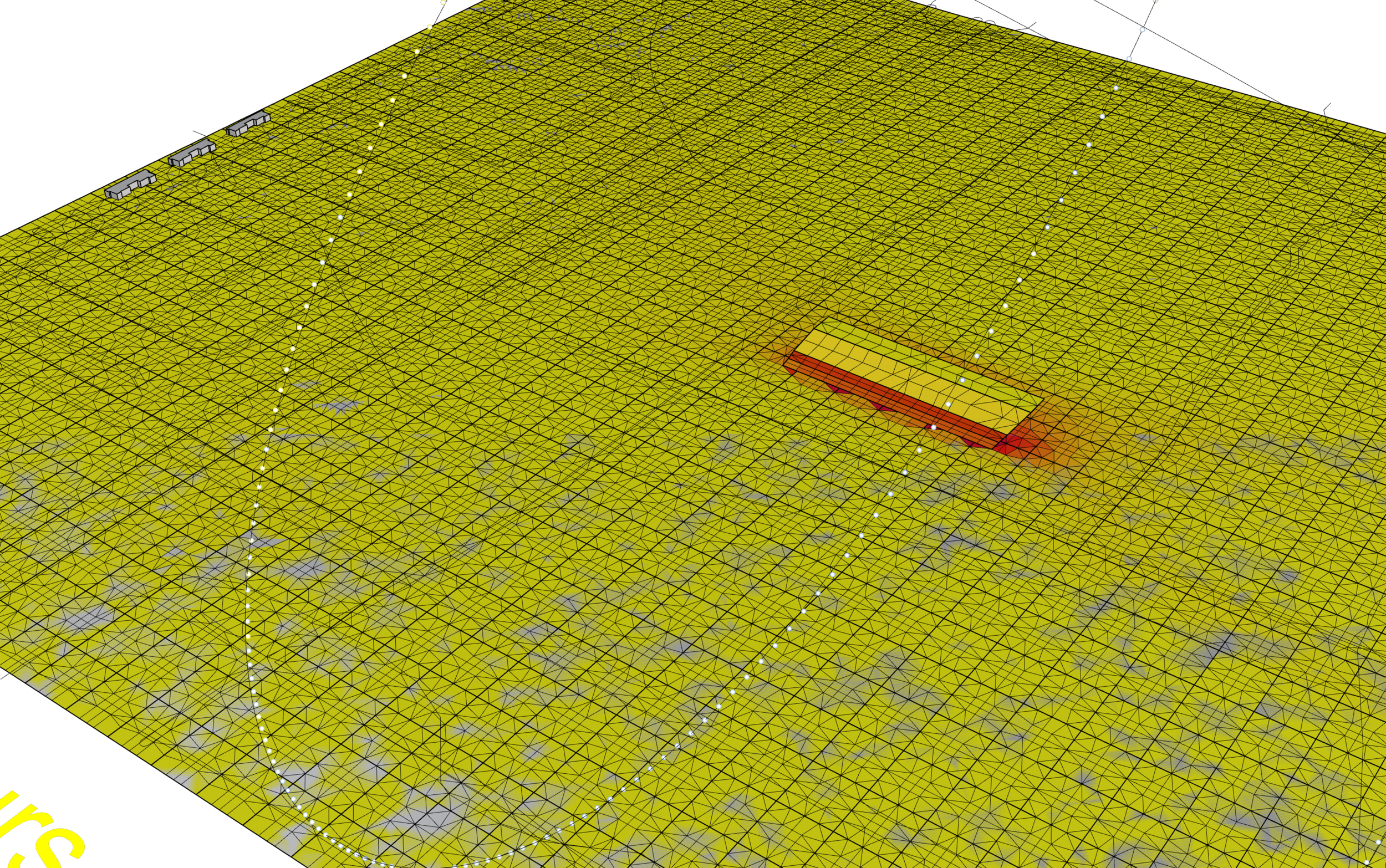

The environmental strategy adopts zoning principles to optimize energy performance and indoor environmental quality (IEQ), by grouping serviced spaces within a deep external envelope along the building edges. Such zoning facilitates precise control over mechanical and natural ventilation, heating, and cooling loads tailored to the diverse functional needs of the factory (Leaman and Bordass, 2007; CIBSE, 2015). Separating the industrial, office, and communal functions into distinct environmental zones allows for targeted environmental controls, reflecting best practice in industrial building design where functional and environmental requirements differ significantly (Gowri et al., 2009). The mechanical ventilation of ground floor factory spaces addresses critical concerns related to dust and contamination control, essential in manufacturing environments (ASHRAE, 2019). The use of filtered ducted fresh air combined with natural cross ventilation on upper floors leverages the temperate climate to reduce energy consumption, providing fresh air supply with minimum mechanical assistance during shoulder seasons (Santamouris, 2013; Givoni, 1998).

Natural Ventilation and Air Movement

The strategy's emphasis on natural ventilation assisted by mechanical fans reflects a hybrid ventilation approach, recognized for improving indoor air quality while minimizing energy consumption (Fuchs et al., 2016). Cross ventilation enabled by the building’s geometry and the spine core air conduits promotes passive cooling, reducing reliance on mechanical systems during mild conditions typical of temperate climates (Givoni, 1998). This approach aligns with current sustainability frameworks promoting mixed-mode ventilation to balance comfort and efficiency (Humphreys and Nicol, 2002).

Daylighting and Solar Control

The environmental design strongly prioritizes maximizing natural daylight to reduce artificial lighting loads and enhance occupant wellbeing, consistent with literature demonstrating that daylight improves productivity and health in workplaces (Boyce, 2014; Lechner, 2015). The use of twin-wall facades and adjustable louvre shading systems enables dynamic solar control, a proven method to optimize daylight penetration while preventing glare and overheating (Harris et al., 2013). Manual and panelized louvre adjustments respond to seasonal variations, aligning with principles of adaptive shading that exploit solar angles for passive heating in winter and shading in summer (Givoni, 1998). The design of glazed roof areas with carefully controlled louvres ensures diffused top-lighting for exhibition and communal spaces, minimizing direct solar gain and creating even illumination, a strategy supported by daylighting research in complex industrial and commercial environments (Mardaljevic, 2000).

Solar Shading and Thermal Comfort

Given the local climate with hot summers and cold dry winters, the deployment of external solar shading on the long facades, including deployable shading panels on rails, reflects advanced passive design strategies that allow fine-tuned control of solar heat gain (Lechner, 2015; Santamouris, 2013). Movable shading systems adapt to changing daylight needs and reduce cooling loads during summer, supporting thermal comfort and energy efficiency (Heschong Mahone Group, 1999). Opaque facade sections accommodate technical and service equipment while maintaining thermal insulation, whereas fully glazed areas maximize daylight harvesting. This duality represents a performance-driven facade design approach optimizing energy conservation without compromising operational flexibility (Carmody et al., 2011).

Airflow Management and Internal Microclimates

The use of ‘spine’ core spaces as air conduits, channeling fresh air from the roof through interstitial spaces to production floors, demonstrates an integrated approach to indoor climate control, leveraging stack effects and thermal buoyancy for natural ventilation (Givoni, 1998). This creates internal microclimates beneficial to air quality and thermal comfort, particularly important in large-scale industrial buildings where uniform conditioning is challenging (CIBSE, 2015). The arrangement of canyon-like circulation routes along the building’s sides not only enhances social interaction and community but also serves as natural ventilation corridors. These “streets” act as ventilation channels, improving airflow through communal zones such as canteens and rest areas, aligning with bioclimatic design principles (Foster et al., 2011).

Option-Specific Environmental Strategies

Option 1 locates environmental zones asymmetrically to match specific functional needs, emphasizing factory-side support facilities and high-level office spaces. This spatial segregation supports tailored HVAC zoning and daylight control according to use patterns, in line with flexible zoning approaches for mixed-use industrial buildings (Leaman and Bordass, 2007). Option 2 centralizes communal support facilities in link blocks above production halls, optimizing daylight access and natural ventilation while reducing energy use through vertical stacking of functions. The alignment of office spaces on one side capitalizes on cross ventilation and daylight (Fuchs et al., 2016). Option 3 simplifies this into continuous bands of support spaces on both sides with terraced upper floors and solar canopies, enhancing solar shading and outdoor rest area usability. This approach integrates environmental comfort with architectural form, promoting social wellbeing and sustainable workplace environments (Carmona, 2019).

References

ASHRAE, 2019. ASHRAE Handbook — HVAC Applications. Atlanta: ASHRAE.

Boyce, P.R., 2014. Human Factors in Lighting. 3rd ed. Boca Raton: CRC Press.

Carmody, J., Cerezo Davila, A. and Reinhart, C.F., 2011. Evaluating the daylight performance of an integrated automated shading and lighting system. Building and Environment, 46(2), pp.389-403.

Carmona, M., 2019. Public Places Urban Spaces: The Dimensions of Urban Design. 3rd ed. London: Routledge.

CIBSE, 2015. Guide A: Environmental Design. 7th ed. London: Chartered Institution of Building Services Engineers.

Foster, J., Wilkins, A. and Stephenson, M., 2011. Sustainable landscape design: Implications for microclimate. Landscape and Urban Planning, 100(1), pp.24-33.

Fuchs, M., Wagner, A. and Hofer, H., 2016. Hybrid ventilation and indoor air quality: The effect of air distribution on airflow and contaminant removal efficiency. Energy and Buildings, 129, pp.1-12.

Givoni, B., 1998. Climate Considerations in Building and Urban Design. New York: Wiley.

Gowri, K., Winiarski, D., Huelman, P. and Gu, L., 2009. Energy and environmental design strategies for manufacturing facilities. ASHRAE Transactions, 115(2), pp.123-135.

Harris, B., Ogulu, D. and Knight, I., 2013. Daylighting and shading controls: A review. Energy Procedia, 42, pp.48-57.

Heschong Mahone Group, 1999. Daylighting in Schools: An Investigation into the Relationship Between Daylighting and Human Performance. Pacific Gas & Electric Company.

Humphreys, M.A. and Nicol, J.F., 2002. The validity of ISO-PMV for predicting comfort votes in every-day thermal environments. Energy and Buildings, 34(6), pp.667-684.

Leaman, A. and Bordass, B., 2007. Are users more tolerant of ‘green’ buildings? Building Research & Information, 35(6), pp.662-673.

Lechner, N., 2015. Heating, Cooling, Lighting: Sustainable Design Methods for Architects. 4th ed. Hoboken: Wiley.

Mardaljevic, J., 2000. Daylight simulation: Validation, sky models and daylight coefficients. Leukos, 1(1), pp.59-79.

Santamouris, M., 2013. Energy and Climate in the Urban Built Environment. London: Routledge.