Theoretical Basis of a Structural Strategy for a Light Industrial Building

Log in to Modern Construction Online for project case study

Prefabrication, Modularity, and Assembly

The proposed structural strategy for the light industrial building is grounded in prefabrication and modular assembly, which are increasingly recognised as pivotal techniques for improving build quality, speed of construction, and site safety (Lawson et al., 2014). The building is conceptualised as a kit-of-parts system, where each component is structurally self-supporting and assembled on site by bolted connections. This approach is highly compatible with transport logistics (both rail and road delivery), and supports rapid on-site assembly without significant wet trades or curing times (Smith, 2010). This prefabrication-driven method also facilitates complex geometric articulation, allowing the design to accommodate shrink-wrapped forms and interlocking volumes. The use of lattice frame modules as both structural and cladding-support elements exemplifies the integration of primary and envelope systems, minimising the need for secondary framing. This not only reduces material usage and cost, but also maximises internal spatial flexibility—a key design goal in light industrial and refurbishment buildings (Kieran & Timberlake, 2004).

Primary and Secondary Structural Hierarchies

The structure is conceived as a dual hierarchy: a primary steel framework comprising major vertical and horizontal members (columns, beams, and platforms), and a secondary system of smaller, modular lattice frames. These secondary frames are formally distinct but structurally independent, allowing architectural freedom and phased construction. This separation aligns with contemporary thinking on hierarchical structural logic, where discrete systems enable both robustness and resilience (Engel, 2007). In this configuration, the primary structure supports the main load-bearing functions—including towers, projecting volumes, and internal floor platforms—while the secondary systems enclose and articulate the spaces with custom-fitted envelope components. Structural independence among systems also simplifies future expansion, particularly relevant in dynamic industrial contexts (Salvadori & Heller, 2002).

Structural Grid Logic and Core Integration

Across all three spatial design options, the structural strategy is founded upon the use of regular structural grids that are designed in coordination with service cores and functional zones. In Option 1, the grid facilitates clear-span spaces between service cores and external façades, accommodating workshop areas, internal meeting rooms, and refurbishment bays. These large, uninterrupted spans are made possible by the use of steel portal frames and moment-resisting connections, which eliminate the need for intermediate supports and maximise interior flexibility (Taranath, 2011).

In Option 2, the strategy is extended vertically with a tower form, necessitating enhanced lateral stability measures such as braced frames or shear walls within the core. The increased height of the office block allows for vertical program stacking while maintaining structural clarity through grid continuity.

In the preferred Option 3, the strategy converges into a unified grid system for the entire building. This offers several design and performance advantages: Structural efficiency through repetition and modularity, thermal bridging minimisation due to integrated cladding support, simplified coordination of mechanical services, vertical risers, and circulation routes. This single-grid system ensures coherence across the podium, refurbishment hall, and tower elements, supporting consistent construction sequencing and architectural expression.

Envelope Integration and Structural Cladding Systems

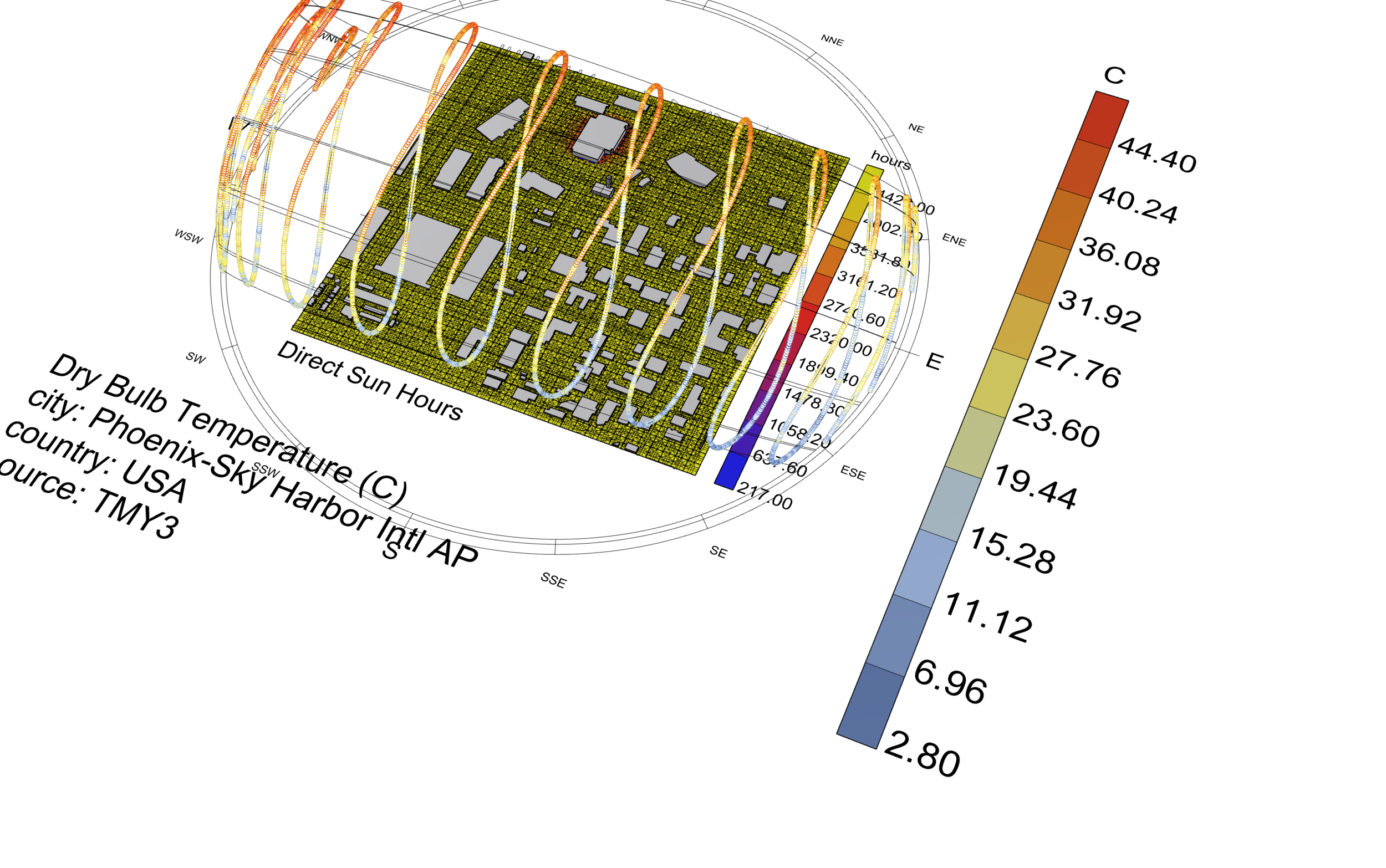

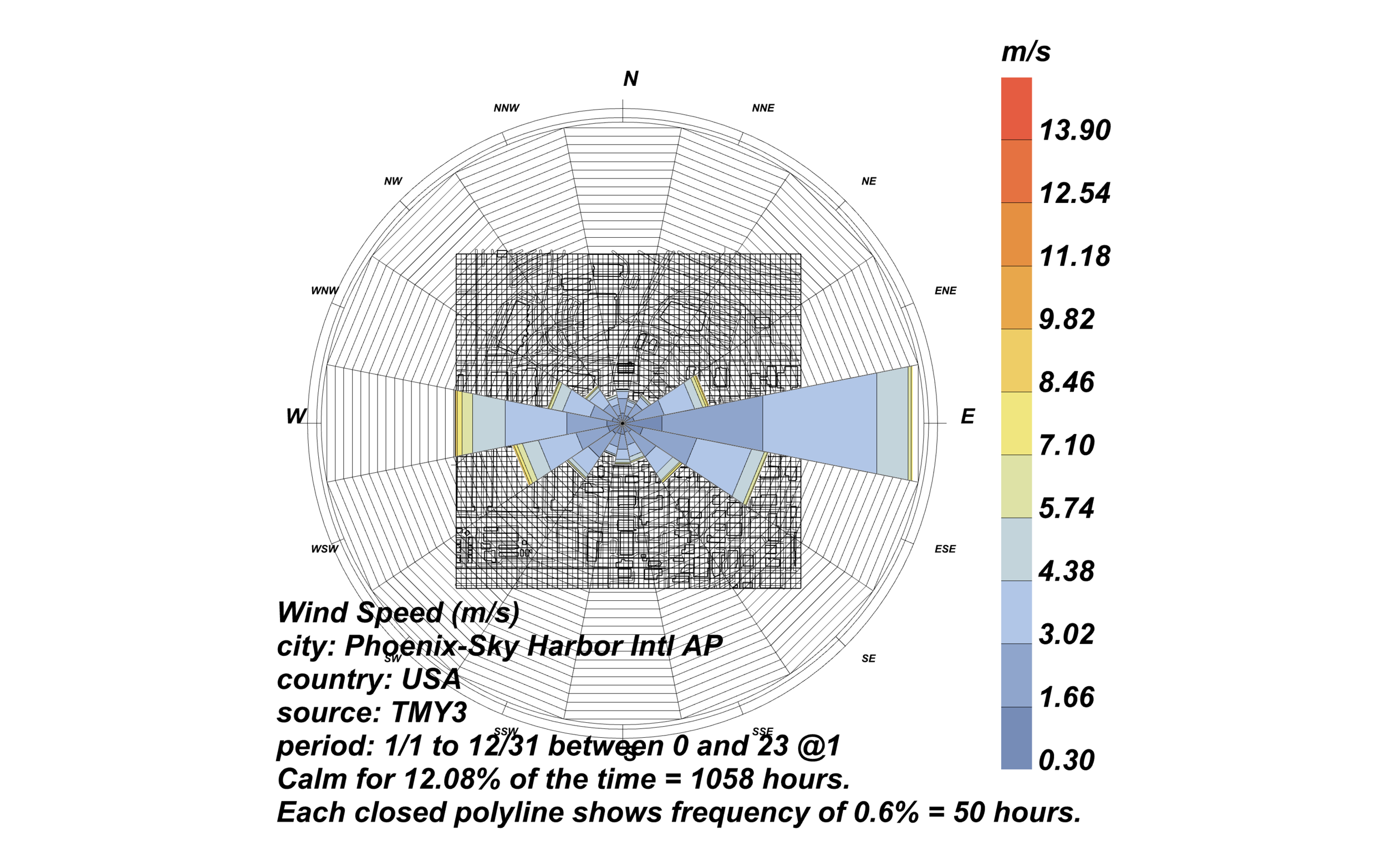

A defining feature of the project is the integration of envelope systems with the primary structure, forming a continuous external skin—referred to as a “shrink-wrapped” design approach. Here, the facade becomes structurally active, eliminating the need for extensive secondary supports. The cladding panels, whether opaque, glazed, or ventilated, are affixed directly to the lattice or portal frame substructure. This methodology aligns with the integrated envelope design paradigm in which structure and skin operate in tandem to achieve performance and formal objectives (Herzog et al., 2004). Moreover, this integrated approach enhances thermal continuity, improves airtightness, and supports energy efficiency—all crucial for buildings in temperate climates, where seasonal variation requires both heating and cooling adaptability (Givoni, 1994).

Structural Adaptability and Functional Zoning

The prefabricated, bolted-together system permits non-disruptive extensions and functional reconfiguration over time. For example, the raised platform for equipment delivery on the upper deck is enabled by cantilevered trusses or steel transfer beams, which can be added or modified as operational needs evolve. This adaptability is particularly advantageous in refurbishment-oriented industrial buildings, where processes and equipment often change (Charleson, 2014). Zoning within the refurbishment and exhibition spaces is supported by the flexible arrangement of service strips and circulation cores, which act as structural anchors while allowing surrounding spaces to adapt to evolving spatial needs. In the tower, vertical loads are concentrated in core walls, allowing floor plates to remain largely free of obstructions.

Overview

The structural strategy for this project demonstrates how modularity, prefabrication, and structural integration can be employed to create a flexible, efficient, and visually expressive building form suited to industrial functions in a temperate climate. The division into primary and secondary systems, the use of shrink-wrapped modular frames, and the embedding of services into a regularised structural grid all serve to create a robust architectural response. This approach not only supports current programmatic needs but also provides a framework for future adaptation, expansion, and architectural richness.

References

Charleson, A. (2014) Structure as Architecture: A Source Book for Architects and Structural Engineers. 2nd edn. London: Routledge.

Engel, H. (2007) Structure Systems. Basel: Birkhäuser.

Givoni, B. (1994) Passive and Low Energy Cooling of Buildings. New York: Wiley.

Herzog, T., Krippner, R. and Lang, W. (2004) Facade Construction Manual. Basel: Birkhäuser.

Kieran, S. and Timberlake, J. (2004) Refabricating Architecture: How Manufacturing Methodologies Are Poised to Transform Building Construction. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Lawson, R.M., Ogden, R.G. and Goodier, C.I. (2014) Design in Modular Construction. London: CRC Press.

Salvadori, M. and Heller, R. (2002) Structure in Architecture: The Building of Buildings. 4th edn. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Smith, R.E. (2010) Prefab Architecture: A Guide to Modular Design and Construction. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Taranath, B.S. (2011) Structural Analysis and Design of Tall Buildings: Steel and Composite Construction. Boca Raton: CRC Press.