Theoretical Basis of a Structural Strategy for a Manufacturing Building

Log in to Modern Construction Online for project case study

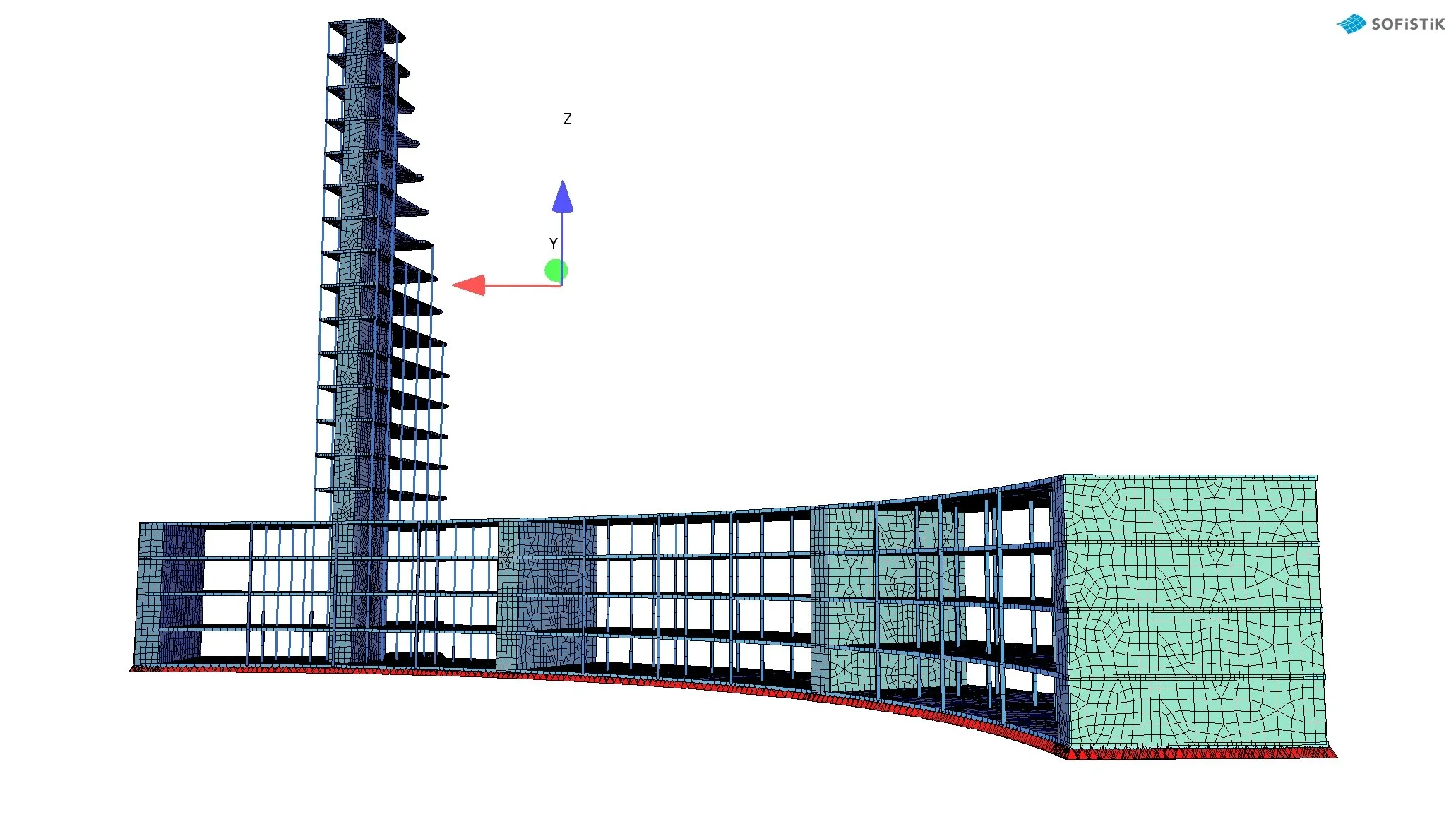

The structural strategy of the proposed manufacturing facility represents a forward-looking synthesis of industrial efficiency, architectural expression, and spatial adaptability. Designed for a temperate climate and incorporating a mix of research, fabrication, and office uses, the building’s structural logic is deeply entwined with its spatial and climatic performance. Central to the strategy is the use of steel-framed systems, trussed hull forms, and lattice or geodesic geometries, all of which are selected to facilitate large, column-free spaces, integrated façade-structure systems, and long-term reconfigurability. This text outlines the theoretical principles underpinning the structural strategy, while identifying specific design opportunities relating to material performance, spatial efficiency, environmental integration, and future-proofing.

The Trussed Hull: An Integrated Envelope-Structure System

At the heart of the structural concept is the steel-framed trussed hull, which forms a tube-like podium block that wraps structure, enclosure, and service infrastructure into a unified whole. This approach moves beyond conventional orthogonal framing—where floor slabs span between regularly spaced columns and beams—and instead exploits the triangulated stiffness of a truss system to enable large, uninterrupted openings along the building’s envelope (Schodek et al., 2014). This “hull” functions similarly to a space frame or diagrid system, where loads are distributed in multiple directions through triangulated members, increasing structural redundancy and reducing the need for internal supports (Engel, 2007). By integrating the façade into the primary structural system, the strategy eliminates the conventional distinction between cladding and frame, creating a load-bearing envelope that allows expressive cut-outs and complex geometries—particularly useful for a technology-driven company wishing to showcase innovation. From a structural engineering perspective, the use of a continuous external shell enhances: Torsional resistance, particularly in asymmetrical or cantilevered forms, lateral stability, reducing the reliance on internal cores, freedom of internal planning, as structure is largely displaced to the periphery. This trussed envelope also accommodates penetrations for staircases, mechanical risers, and light wells, enabling functional and spatial integration without compromising structural continuity.

Steel-Framed Consoles and Bridge Structures

The incorporation of bridging elements between blocks, supported on steel-framed consoles, offers a flexible means of spanning across service yards or open ground while maintaining clear floor plates. This approach is enabled by the inherent advantages of steel in bending and tension, allowing for relatively slender supports and long-span configurations with minimal deflection (Allen and Iano, 2019). Cantilevered structures supported by steel consoles present specific structural opportunities: They allow for column-free interiors, critical in manufacturing and R&D spaces requiring spatial reconfiguration, they offer the potential for articulated shading devices or overhangs to modulate solar gain—a key consideration in temperate climates with seasonal sun angles, they permit architectural expression, forming dramatic entryways, viewing platforms, or suspended walkways.

Core Integration and Spatial Distribution

Stair cores, escape routes, washrooms, and services are located within zigzag configurations that interlock with the trussed hull. This placement allows vertical circulation and utilities to be housed within the structural grid, reducing spatial wastage and simplifying service routing. Cores located within the structural envelope contribute to lateral stability through the use of braced steel cores—a common high-performance solution in hybrid office/industrial buildings (Macdonald, 2001). Diagonal bracing within cores can be easily concealed behind opaque walls flanking vertical slot windows, maintaining visual consistency while enhancing seismic and wind resistance. In the wedge-shaped tower, the central spine of service cores divides the plan into two operational halves and acts as the main vertical stabilising element. This configuration allows: Clear separation of service and production zones, structurally independent floor wings, enabling staged construction or future expansion, integration of vertical MEP systems within the core structure, improving maintenance access and reducing floor-to-floor height.

Composite Floor Systems and Lattice Frames

Both the wedge tower and the engineering modules atop the bridges use steel-framed floors with metal deck composite construction. This well-established system offers: reduced dead load compared to concrete slabs, enhanced stiffness through composite action between steel beams and concrete topping, speed of construction, due to prefabricated deck panels and fast on-site assembly. The perimeter of these structures is formed by lattice frames and geodesic frames, offering several structural advantages: Weight efficiency, due to the use of triangulated geometry, visual transparency, maintaining lightness in massing while enclosing large spans (Fuller, 1961), ease of prefabrication, since the modular nodes and members can be manufactured off-site. Geodesic and lattice envelopes also facilitate integration of service platforms and air intake/exhaust ducts, supporting functional needs while maintaining the architectural language of engineered precision.

Solar Control and Environmental Performance

Cantilevered forms and angled façades are not purely aesthetic but serve to modulate solar exposure, especially at glazed end walls. In a temperate climate, buildings must respond to both high summer sun and low winter angles. Structural overhangs—whether through consoles, deep truss members, or lattice projections—enable passive solar shading (Watkins, 2010). Mechanical baffles mounted to the rooflight structure within the trussed hull provide controlled daylight admission into the internal volume, reducing glare while minimising the energy load for artificial lighting. These systems may be integrated structurally into the truss upper chords or tension cable systems, offering opportunities for kinetic facades or adjustable light modulation (Kolarevic, 2003).

Modularity, Expandability, and Future-Proofing

One of the most significant structural opportunities presented in all three design options is modular adaptability:

Option 1 employs rectilinear steel portal frames, allowing open-span industrial units to be reconfigured or converted into office spaces. This follows the classic universal frame grid model, designed to accommodate change (Curtis, 2010).

Option 2 treats each building as an independent structural entity, with two link buildings that can be added or dismantled. This facilitates phased construction and incremental expansion, a key benefit for growing manufacturing operations.

Option 3 introduces a looped, curvilinear configuration, with vertical expansion (adding floors to office zones) and lateral expansion (extending the loop or podium). The continuous nature of the podium structure allows it to be expanded in modular increments using the same trussed envelope logic, aligning with principles of open building design (Habraken, 1998). By deploying a consistent structural system (steel frames with composite floors, trussed envelopes, and service cores), the design allows for standardisation of construction components, enabling rapid adaptation to future needs.

Overview

The structural design of this manufacturing and R&D facility demonstrates how advanced steel systems, modular components, and integrated cores can be synthesised to support not only technical requirements but also environmental performance and architectural ambition. The use of trussed hulls, lattice frames, and steel-framed consoles reflects a deep engagement with the structural language of industry, while allowing for flexibility, daylighting, and operational clarity. This theoretical framework supports a building typology that is resilient, adaptive, and expressive, offering a powerful case study in the structural design of next-generation manufacturing environments.

References

Allen, E. and Iano, J. (2019). Fundamentals of Building Construction: Materials and Methods. 7th ed. Hoboken: Wiley.

Curtis, W. (2010). Architectural Structures. London: Laurence King.

Engel, H. (2007). Structure Systems. Ostfildern: Hatje Cantz.

Fuller, R.B. (1961). Geodesic Structures. New York: Princeton Architectural Press.

Habraken, N.J. (1998). The Structure of the Ordinary: Form and Control in the Built Environment. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Kolarevic, B. (2003). Architecture in the Digital Age: Design and Manufacturing. New York: Taylor & Francis.

Macdonald, A.J. (2001). Structure and Architecture. 2nd ed. Oxford: Architectural Press.

Schodek, D.L., Bechthold, M., Griggs, K., Kao, K.M. and Steinberg, M. (2014). Structures. 7th ed. Boston: Pearson.

Watkins, R. (2010). Steel Design Handbook: ASD, LRFD, and LRFD-AISI Specifications. Boca Raton: CRC Press.