Theoretical Basis of a Structural Strategy for an Office Building in a hot dry climate

Log in to Modern Construction Online for project case study

The structural design of this building demonstrates a performative integration of architectural form and structural system, in which reinforced concrete, steel, and post-tensioned elements are combined to achieve both spatial flexibility and environmental responsiveness in a dry, hot climate. The design leverages structural form not only for load-bearing efficiency but also for solar control, ventilation routing, and visual organisation—all critical in a climate typified by high solar radiation and low humidity (Olgyay, 2015; Lechner, 2014).

Core-Periphery Strategy: Shear Walls as Structural and Environmental Elements

The use of side-positioned reinforced concrete shear walls that form a wrap around the tower constitutes a core-periphery structural strategy, enabling column-free interior spaces and optimising the building’s resistance to lateral forces such as wind and seismic activity (Friedman, 2010; Allen and Iano, 2019). This arrangement allows the central floor plates to remain highly adaptable for changing programmatic needs, aligning with contemporary workplace design principles (Kolarevic and Malkawi, 2005). These shear walls, clad in glass-fibre reinforced concrete (GFRC), double as thermal mass buffers, absorbing heat during the day and releasing it during cooler night periods—a key passive design strategy for hot, dry climates (Givoni, 1994). Their opaque surface treatment and thickness also reduce direct solar gain, enhancing indoor comfort and lowering cooling loads. The placement of glazed slots between shear wall elements introduces daylight without compromising the walls’ structural or thermal integrity, facilitating controlled daylight penetration and cross-ventilation potential (Lechner, 2014).

Vertical Integration: Post-Tensioned Slabs and Structural Continuity

The tower structure incorporates post-tensioned concrete slabs, spanning between the side shear walls and externally expressed service pods. Post-tensioning allows for larger slab spans with reduced thickness, minimizing floor-to-floor heights and the total volume to be cooled—important in climates where cooling demand dominates (Schodek et al., 2014). By extending the same post-tensioned structural system into the podium, a strong visual and structural continuity is established. The movement joint between tower and podium is critical for managing differential settlement, thermal expansion, and seismic performance—especially as the tower and podium vary in scale, mass, and function (Hegger et al., 2008). This continuity eliminates the need for transfer structures between tower and podium, reducing structural complexity and cost while improving performance under thermal and seismic stresses. The decision to align structural grids and forms across tower and podium enables vertical load continuity and rationalises services and circulation routes (Salvadori and Heller, 1975).

Multi-System Strategy: Concrete and Steel for Diverse Programme Requirements

Each design option leverages a composite structural strategy suited to the programme it supports. In Option 1, the podium houses prototyping halls that require long-span steel trusses for large, column-free spaces. These are supported on double rows of concrete columns, enabling side-access galleries and providing a regular structural rhythm that aligns with façade articulation. Option 2 separates the volumes into distinct structural systems—concrete-framed service spaces, steel-trussed manufacturing halls, and a concrete-framed office tower—an approach which allows optimised column grids and spans for each functional block. Option 3 hybridises these strategies, allowing modular column systems and repetition of truss-based roofs in the halls while maintaining a consistent grid in the office tower. This creates opportunities for fabrication efficiency and on-site construction sequencing, especially useful in climates with short construction windows due to thermal extremes (Charleson, 2005). These strategies permit the building to accommodate 'structures within structures'—nested substructures that can be independently constructed and serviced. This separation simplifies construction phasing and enables greater thermal and acoustic zoning, essential in mixed-use buildings that include both industrial and office functions (Kolarevic and Malkawi, 2005).

Structural Expression and Environmental Legibility

The structural system is expressed architecturally, where opaque reinforced concrete volumes and climatic ‘bookends’ are used to visually signify functional zones such as service cores and shear wall structures. This echoes the tectonic tradition in architecture, where structure is both functional and expressive (Frampton, 2001). The building’s formal articulation—three vertically stacked volumes in the tower and three horizontal rooftop volumes in the podium—provides legibility and supports solar orientation strategies. Glazed areas are inset or shaded by protruding elements, while massive wall zones provide passive solar control and mechanical shaft integration. The visual differentiation of tower zones—opaque vs. glazed, shaded vs. exposed—communicates where solar heat gain is mitigated and where daylight is introduced, aligning the architectural image with passive performance strategies (Yeang, 1999).

Climate-Responsive Structural Form

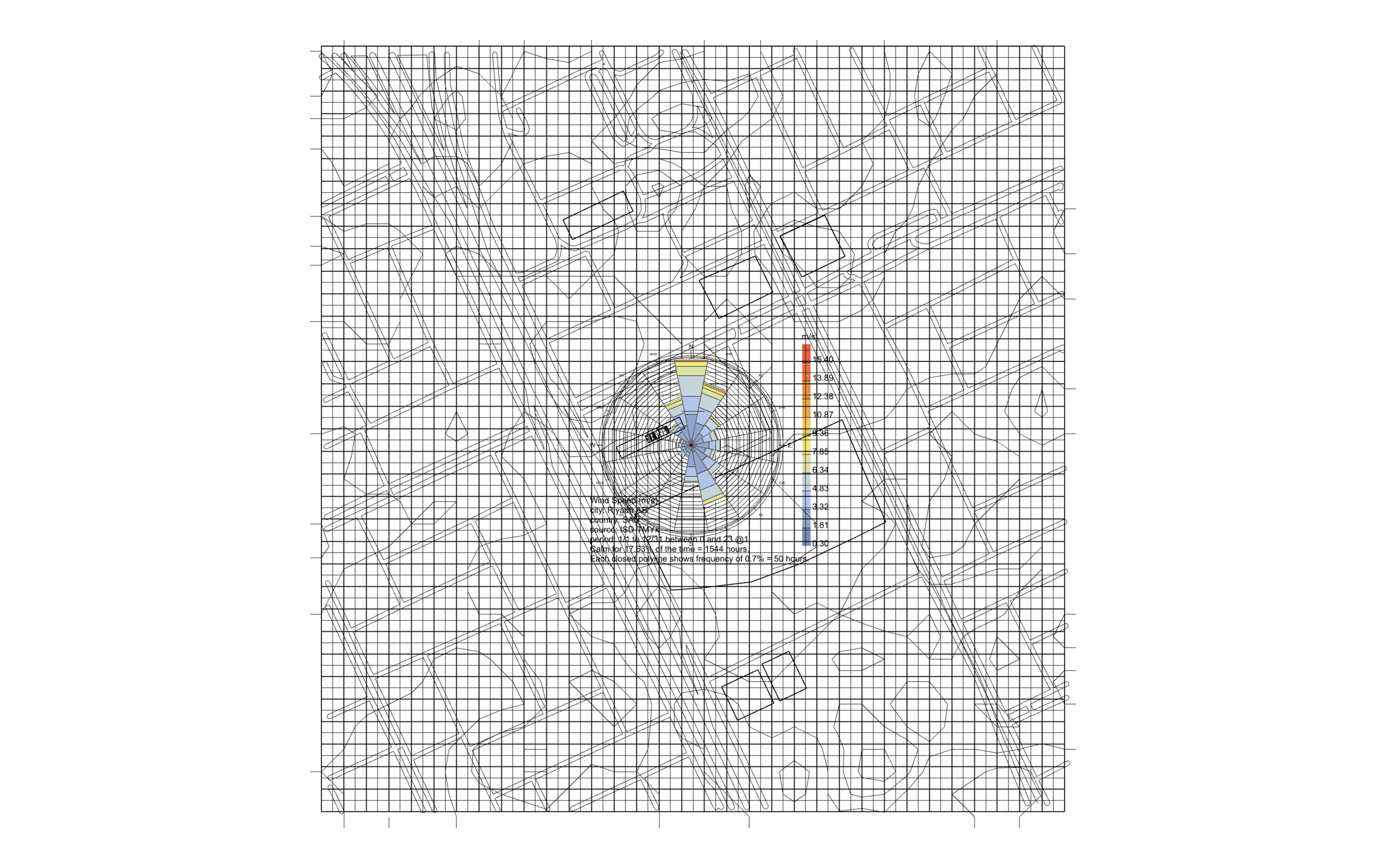

In arid climates, the use of thermal mass, shaded voids, and deep façades is central to environmental control. The structural forms—especially the concrete side walls and recessed galleries—create deep zones that delay solar penetration and allow for diurnal temperature balancing. Externally expressed galleries, particularly those in Option 3, use double rows of columns to create shaded intermediate spaces that reduce heat loads on external walls while offering passive air pathways. These shaded zones function as thermal buffers, reducing energy demand for cooling and improving occupant comfort (Olgyay, 2015; Givoni, 1994). The independent structural pods—such as the ‘backpacks’ flanking the tower—serve not only as service enclosures but also as insulated mass elements, shielding internal spaces from solar exposure and providing vertical service distribution without overheating internal cores.

Avoiding Transfer Structures: Efficiency through Structural Independence

One of the critical efficiencies in the structural concept is the avoidance of internal transfer structures. By designing discrete but coordinated structural systems for each programme—tower, podium, prototyping halls—engineers eliminate the need for heavy and complex transfer slabs or beams, which are expensive, increase structural depth, and often perform poorly under seismic or thermal movement (Schodek et al., 2014).Instead, the approach of nested independent structures enables the building to settle independently, respond to thermal expansion differently, and simplify construction logistics, especially in remote or hot-climate contexts where labour and material efficiency are key (Hegger et al., 2008).

Overview

This structural strategy exemplifies a synthesis of programmatic diversity, climatic responsiveness, and visual coherence. Through the combined use of shear walls, post-tensioned slabs, and long-span trusses, the design responds directly to the spatial needs of the building, while offering environmental moderation in a hot, dry climate. The integration of structural logic with architectural form creates a legible, high-performance building that communicates its own organisation and sustainability strategies through its structural expression.

References

Allen, E. and Iano, J. (2019). Fundamentals of Building Construction: Materials and Methods. 7th ed. Hoboken: Wiley.

Charleson, A. (2005). Structure as Architecture: A Source Book for Architects and Structural Engineers. Oxford: Elsevier.

Frampton, K. (2001). Studies in Tectonic Culture: The Poetics of Construction in Nineteenth and Twentieth Century Architecture. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Friedman, D. (2010). Structure and Design. New York: Norton.

Givoni, B. (1994). Passive and Low Energy Cooling of Buildings. New York: Wiley.

Hegger, M., Fuchs, M., Stark, T. and Zeumer, M. (2008). Energy Manual: Sustainable Architecture. Basel: Birkhäuser.

Kolarevic, B. and Malkawi, A. (eds.) (2005). Performative Architecture: Beyond Instrumentality. New York: Routledge.

Lechner, N. (2014). Heating, Cooling, Lighting: Sustainable Design Methods for Architects. 4th ed. Hoboken: Wiley.

Olgyay, V. (2015). Design with Climate: Bioclimatic Approach to Architectural Regionalism. Updated ed. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Salvadori, M. and Heller, R. (1975). Structure in Architecture. 3rd ed. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall.

Schodek, D., Bechthold, M., Griggs, K., Kao, K.M. and Steinberg, M. (2014). Structures. 7th ed. London: Pearson.

Yeang, K. (1999). The Green Skyscraper: The Basis for Designing Sustainable Intensive Buildings. Munich: Prestel.