Theoretical Basis of a Structural Strategy for a Mini-Tower Residential Cluster

Log in to Modern Construction Online for project case study

The structural strategy for this residential tower project—conceived as five interconnected mini-towers—demonstrates a sophisticated synthesis of form, function, and fabrication logic. By combining reinforced concrete and steel framing systems, the design accommodates a complex architectural geometry, optimises material performance, and enhances environmental responsiveness. The project presents a forward-thinking case for distributed cores, perimeter framing, and service-based structural zoning, all within the context of high-density living in a temperate climate.

Multi-Tower Form and Hybrid Materiality

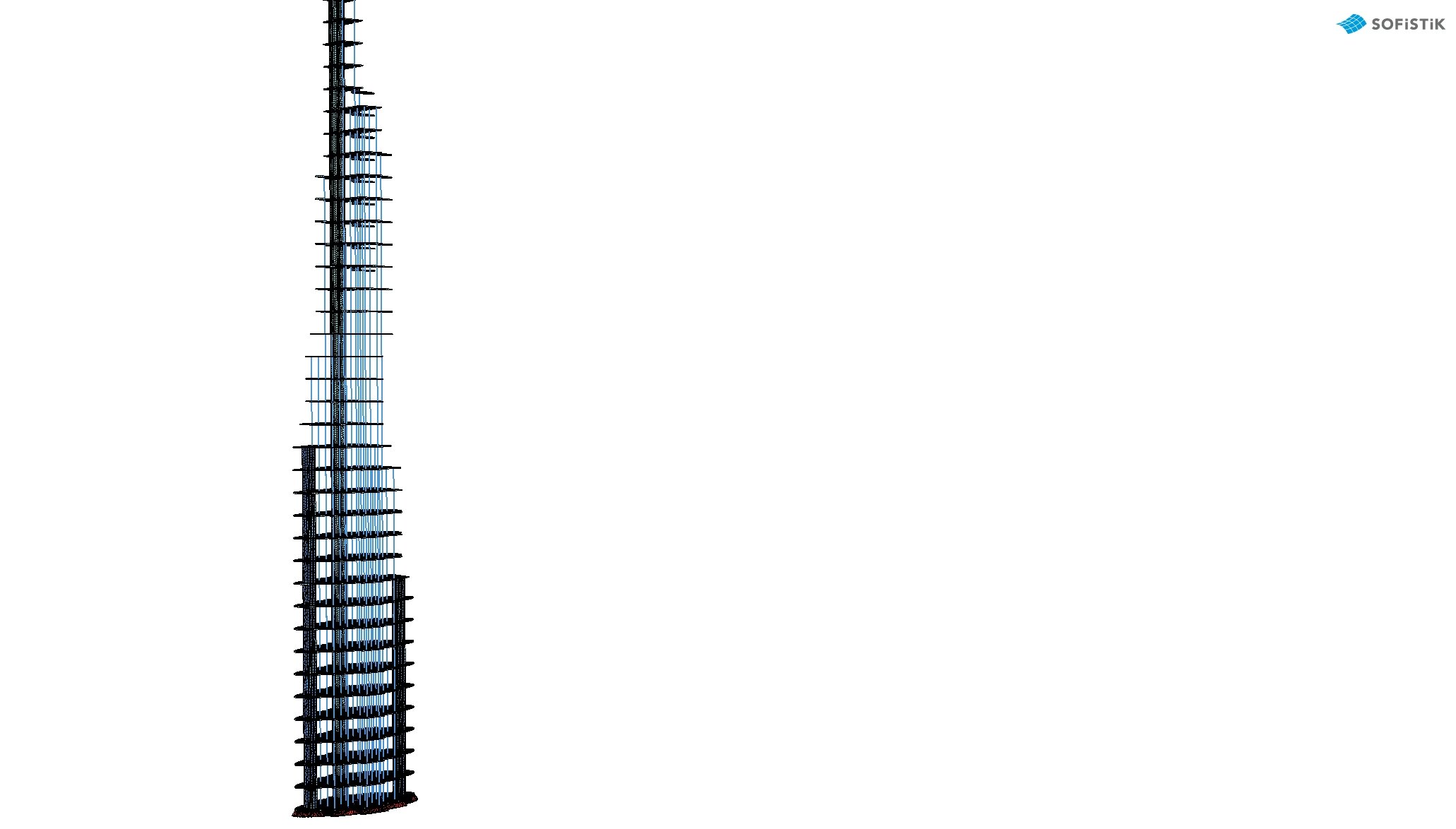

The arrangement of five vertically differentiated mini-towers creates a sculptural skyline, wherein each volume terminates at a different height. This topological variation reduces perceived mass, offers wind load mitigation, and introduces vertical segmentation that aligns with structural zoning. Only one tower reaches the maximum height, concentrating structural loads in a controlled manner and allowing others to taper or terminate earlier—a strategy that alleviates overturning moments and minimises peak load accumulations at the base (Smith & Coull, 1991). The hybrid structural system—reinforced concrete for the lower volumes and steel framing for the upper levels—capitalises on the complementary properties of each material. Concrete provides mass and stiffness at the base, ideal for resisting lateral loads and anchoring the overall structure (Taranath, 2011). The transition to steel framing at upper levels reduces dead loads, improves constructability for complex geometries, and allows long-span solutions and curved members with greater fabrication flexibility (Salvadori & Heller, 1986; CTBUH, 2018).

Shaped Structures and Expressive Geometry

To articulate the curved and inclined architectural forms—particularly at the upper levels—curved steel members are employed along floor edges and roof slopes. These members enable the roofline to become a functional bracing zone, reinforcing the structure while contributing to its distinctive silhouette. This geometry is not purely aesthetic; the use of angled and triangulated forms at roof level enhances the building's aerodynamic performance, distributing wind pressures and reducing oscillation frequencies common in slender towers (Ali & Moon, 2007). The use of shaped steel structures to “wrap” habitable volumes—especially at the perimeter—transforms the façade into a structural enclosure, forming what is effectively a 'trussed hull'. This concept draws from naval and aerospace engineering, where exoskeletal frames carry both environmental enclosures and structural loads (Engel, 2007). By integrating vertical, inclined, and diagonal members along the façade, the structure acts as both skin and skeleton—reducing the need for internal perimeter columns and freeing the interior plan.

Service Integration and Structural Economy

A key innovation in the design is the externalisation of services. Staircases, risers, and HVAC routes are removed from apartment interiors and positioned within service spines on the building’s exterior. These zones are structurally autonomous but integrated with the primary façade system. Prefabricated stair and service modules are mounted onto the primary frame, reducing the structural demands of cast-in-place voids, eliminating secondary beams, and simplifying load paths (Gibson, 2010). This approach offers a high degree of spatial flexibility. Internal floorplates are freed from intrusive structural elements, enabling modular apartment layouts and duplex configurations. The central concrete core—used to carry vertical and lateral loads—becomes a strategic stabilising element, complemented by the braced exoskeletal façade. This dual approach—core-plus-perimeter—is particularly effective in asymmetrical or non-uniform tower geometries where a traditional centralised core is insufficient to counter torsion or drift (Taranath, 2011; Moon, 2008). Moreover, by using the primary structure to support only the habitable floorplates, and separating services structurally and spatially, the building avoids the complex detailing required for penetrations and openings within floor structures—reducing cost, complexity, and risk. Although this increases the cost of external staircase and service structures, the trade-off in construction simplicity, access, and performance is economically and operationally advantageous (CTBUH, 2018).

Prefabrication and Maintenance Accessibility

The service spines are not only architecturally expressive, but also operationally strategic. Their visibility and separation from residential spaces permit independent access for maintenance personnel, reducing disruption to occupants. This principle echoes emerging best practices in resilient housing design, where distributed systems allow zones of the building to remain operational even under partial failure or during maintenance (Gann et al., 2011). The use of prefabricated elements—including service shafts, stair modules, and façade components—further accelerates construction and improves dimensional accuracy and material efficiency. Modular construction also supports circular economy strategies, allowing components to be replaced or upgraded over time without compromising the core structure (Wang et al., 2020).

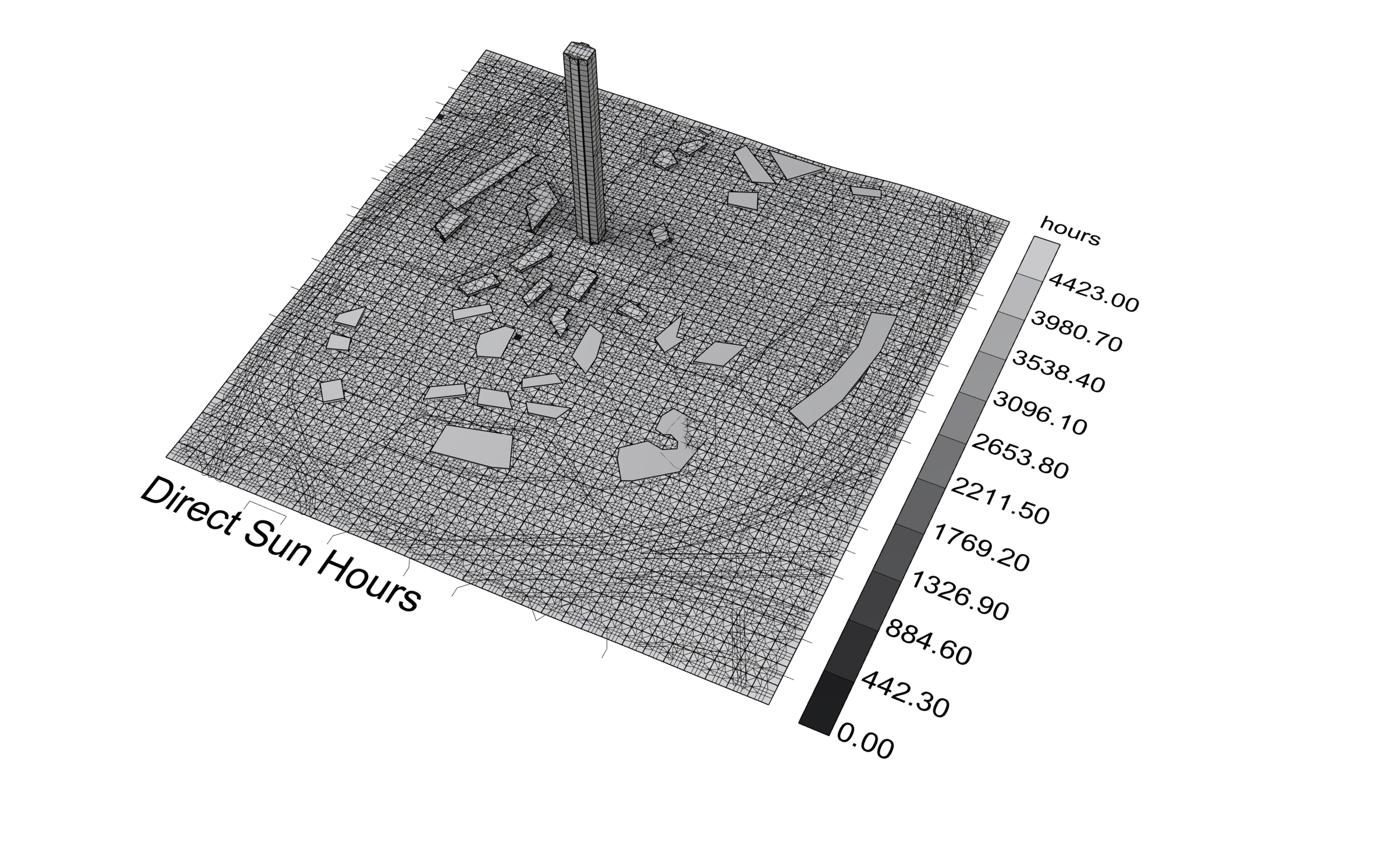

Environmental Synergy: Passive Systems and Structural Zoning

The zoning of services and the distributed structural design enable environmental responsiveness that is uncommon in high-rise residential buildings. The external service spines support passive ventilation shafts and stack ventilation systems that run the height of the tower, supplementing active mechanical systems. By not concentrating all services at roof level—where maintenance and access are more challenging—the building permits distributed plant systems, improving thermal zoning, pressure balancing, and energy efficiency (Yeang, 2006). Inclined and recessed roof geometries also allow for the integration of solar technologies, greywater harvesting systems, and green roofs, without interfering with key structural zones. The structural and environmental strategies reinforce one another: diagonal structural frames provide ideal fixing lines for glazing supports, PV mounts, and maintenance tracks—turning the entire external structure into a multifunctional layer.

References

Ali, M.M. & Moon, K.S. (2007). Structural Developments in Tall Buildings: Current Trends and Future Prospects. Architectural Science Review, 50(3), pp. 205–223.

CTBUH (Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat). (2018). Tall Buildings + Urban Habitat: Volume 2. London: Routledge.

Engel, H. (2007). Structure Systems. 3rd ed. Basel: Birkhäuser.

Gann, D.M., Salter, A.J. & Whyte, J.K. (2011). Design Quality in New Housing: Learning from the Netherlands. London: Taylor & Francis.

Gibson, R. (2010). Structural Engineering for Architects: A Handbook. London: Springer.

Moon, K.S. (2008). Optimal Grid Geometry of Diagrid Structures for Tall Buildings. Architectural Science Review, 51(3), pp. 239–251.

Salvadori, M. & Heller, R. (1986). Structure in Architecture: The Building of Buildings. 3rd ed. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Smith, B.S. & Coull, A. (1991). Tall Building Structures: Analysis and Design. New York: Wiley.

Taranath, B.S. (2011). Structural Analysis and Design of Tall Buildings: Steel and Composite Construction. Boca Raton: CRC Press.

Wang, L., Zhang, M. & Li, H. (2020). Modular Construction: From Projects to Products. Automation in Construction, 114, 103197.

Yeang, K. (2006). Ecodesign: A Manual for Ecological Design. London: Wiley-Academy.