Theoretical Basis: Environmental Strategy and Design Opportunities for a Retail Centre

Log in to Modern Construction Online for project case study

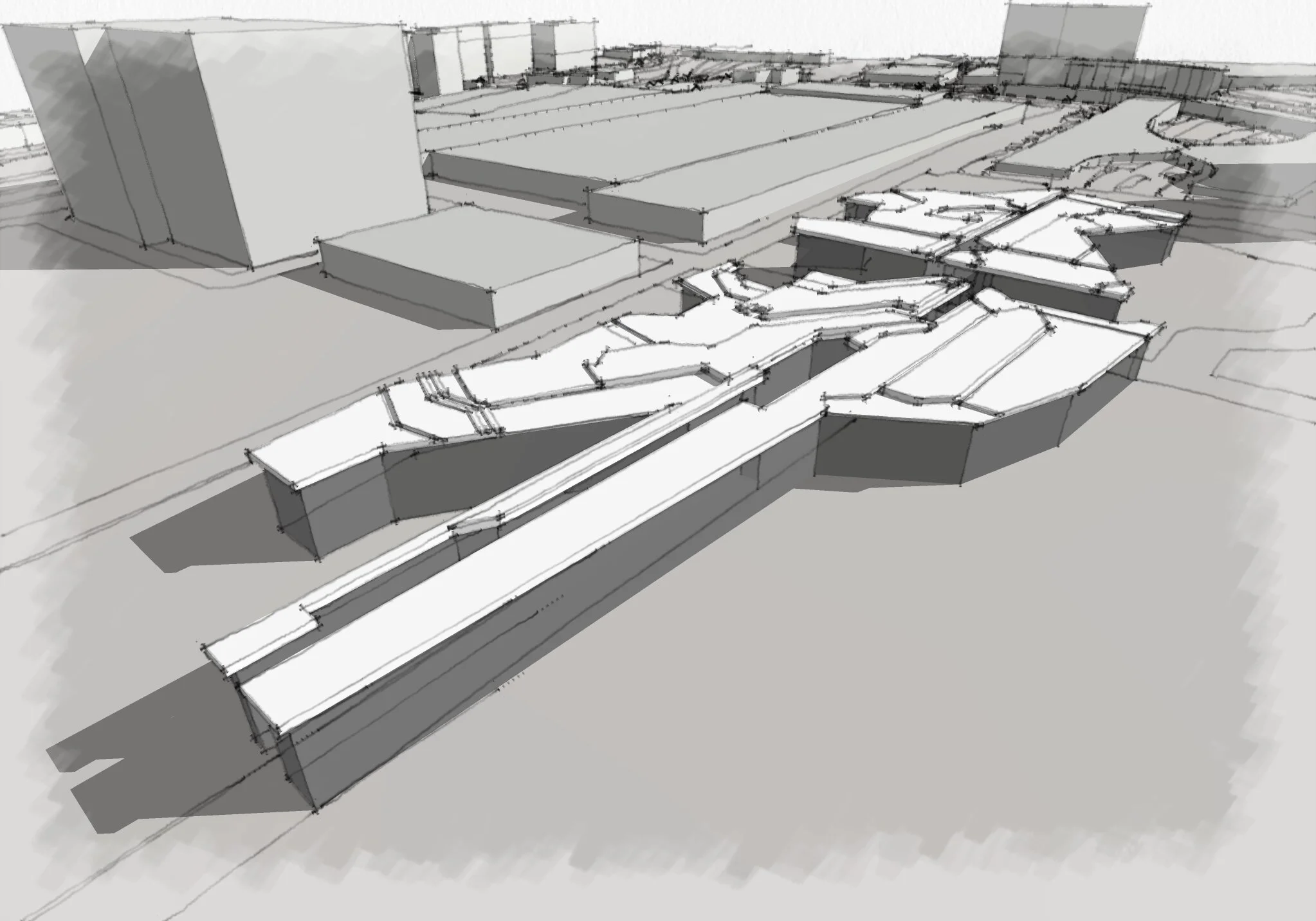

Mechanical Ventilation and Roof-Level Service Distribution

The environmental strategy employs a mechanical ventilation system serviced from the roof level, with ducted air distribution routed through interstitial spaces between building volumes and facades. This approach aligns with principles of modular and flexible service integration, allowing for reduced duct lengths, minimized thermal losses, and enhanced maintainability (Lechner, 2014). Positioning ductwork between inner and outer facades also contributes to a buffer zone effect, reducing thermal transmittance through the building envelope and aiding in temperate climate moderation (Givoni, 1994). Utilizing the roofscape as a network for distributing HVAC, electrical, and water services is consistent with advanced environmental design frameworks promoting adaptability and decentralization (Szokolay, 2008). This strategy facilitates rapid reconfiguration of tenant spaces without requiring extensive disruption of service infrastructure, a key advantage for retail centres with evolving operational needs (Cole and Sterner, 2000). The reduced size of air handling units and chillers, enabled by shorter duct runs, contributes to energy efficiency by lowering fan power consumption and minimizing conditioning losses (ASHRAE, 2016).

Flexibility through Environmental Zoning and Independent Unit Services

The division of the retail centre into distinct environmental zones — notably canyons as buffer spaces and differentiated blocks according to solar orientation and usage — reflects a refined application of thermal zoning strategies to optimize energy use and occupant comfort (Lechner, 2014; Hegger et al., 2008). Buffer zones moderate temperature gradients between retail units, reducing simultaneous heating and cooling demands and enabling passive load balancing within the building envelope (Givoni, 1994). Incremental refinement of zoning from Option 1 to Option 3 demonstrates an evolving strategy towards microclimate control, responding to the specific thermal and humidity requirements of diverse retail and food service functions. This mirrors best practices in climate-responsive design, which advocates nuanced environmental management aligned with spatial function and orientation to reduce overall energy intensity (Szokolay, 2008).

Individualized Environmental Control and Tenant Flexibility

Treating each retail unit as an independently serviced space resembles a “street-like” model of environmental control, where units operate as discrete entities within a shared infrastructure. This modular approach supports tenant-specific climate control, enabling precise adjustments to ventilation rates, thermal comfort parameters, and occupancy changes (Lechner, 2014). Such flexibility is vital in retail environments where different tenants have varying HVAC demands, from food courts requiring high ventilation to typical retail needing moderate air changes (ASHRAE, 2016). The roof-level distribution system allows for shared or isolated air supply configurations, fostering energy efficiency through demand-controlled ventilation (DCV) and enabling tenants to draw on centrally conditioned air or augment with fresh air from the canyons for natural ventilation (Cole and Sterner, 2000). This hybrid approach aligns with emerging trends in adaptive environmental control systems that balance energy conservation with occupant well-being (Fisk, 2000).

Environmental Buffers and Natural Ventilation Integration

Using circulation canyons as environmental buffer zones with controlled temperature and humidity provides opportunities for semi-conditioned transitional spaces that reduce heating and cooling loads on adjacent retail units (Gehl, 2011). This concept resonates with climate-responsive urban design, where intermediate spaces mitigate harsh outdoor conditions while offering comfortable pedestrian environments year-round (Givoni, 1994). Moreover, the ability for tenants to draw air from the central canyon spaces to augment mechanical ventilation introduces a natural ventilation strategy that can reduce mechanical cooling loads during mild periods common in temperate climates (Hegger et al., 2008). Such mixed-mode ventilation approaches have been shown to improve indoor air quality and thermal comfort, while enabling energy savings (Fisk, 2000; Lechner, 2014).

Adjusting Thermal Setpoints to Reflect Contemporary Retail Trends

The environmental strategy acknowledges the evolving trend in retail towards wider temperature tolerances, allowing interior air temperatures to be cooler in winter and warmer in summer than traditionally maintained (Leaman and Bordass, 2007). This adaptation reflects growing understanding that strict temperature control often leads to excessive energy use without corresponding occupant satisfaction, especially in transient, publicly accessed retail environments (ASHRAE, 2016). This trend supports energy reduction while maintaining comfort through localized environmental controls and adaptive comfort models (de Dear and Brager, 2002).

Overall strategy

The environmental strategy detailed for the retail centre integrates mechanical ventilation with innovative roof-level service distribution, creating a highly flexible, energy-efficient building system suited for a temperate climate. Through careful zoning, buffer space creation, and individualized tenant control, the design balances operational adaptability with occupant comfort and sustainability objectives. The incorporation of natural ventilation pathways and a modern approach to thermal setpoints further enhances the environmental performance and user experience of the retail environment.

References

ASHRAE (2016) ASHRAE Handbook—HVAC Systems and Equipment. Atlanta, GA: American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers.

Cole, R.J. and Sterner, E. (2000) ‘Reconciling theory and practice of flexible building services,’ Building Research & Information, 28(2), pp. 114–127.

de Dear, R.J. and Brager, G.S. (2002) ‘Thermal comfort in naturally ventilated buildings: revisions to ASHRAE Standard 55,’ Energy and Buildings, 34(6), pp. 549–561.

Fisk, W.J. (2000) ‘Health and productivity gains from better indoor environments and their relationship with building energy efficiency,’ Annual Review of Energy and the Environment, 25(1), pp. 537–566.

Gehl, J. (2011) Life Between Buildings: Using Public Space. Washington, DC: Island Press.

Givoni, B. (1994) Passive and Low Energy Cooling of Buildings. New York: Wiley.

Hegger, M., Fuchs, M., Stark, T. and Zeumer, M. (2008) Energy Manual: Sustainable Architecture. Basel: Birkhäuser.

Leaman, A. and Bordass, B. (2007) ‘Are users more tolerant of ‘green’ buildings?’ Building Research & Information, 35(6), pp. 662–673.

Lechner, N. (2014) Heating, Cooling, Lighting: Sustainable Design Methods for Architects. 4th ed. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Szokolay, S.V. (2008) Introduction to Architectural Science: The Basis of Sustainable Design. 2nd ed. Oxford: Architectural Press.