Theoretical Basis of an Environmental Strategy for a Hotel

Log in to Modern Construction Online for project case study

Zoning and Environmental Control

The division of the building into discrete environmental zones, with each apartment considered a single thermal and ventilation zone and circulation spaces forming separate zones, aligns with best practices in energy-efficient building design (Lechner, 2015). Zoning allows tailored control of heating, ventilation, and air conditioning (HVAC) systems, reducing energy consumption by avoiding the conditioning of unoccupied or low-use spaces (ASHRAE, 2019). The mixed strategy of mechanical and natural ventilation in habitable rooms maximizes occupant comfort and air quality while minimizing energy use. Natural ventilation is employed seasonally, especially in summer, via operable vents, enabling passive cooling and reducing reliance on mechanical systems (Givoni, 1998). Mechanical ventilation with heat recovery maintains indoor air quality and energy efficiency during colder months by retaining heat while exchanging stale air, crucial in tightly insulated buildings (Feist and Peper, 2016; CIBSE, 2015).

High Thermal Insulation and Controlled Glazing

A highly insulated opaque envelope, combined with limited but strategically shaped glazing, balances thermal performance and occupant wellbeing. Minimizing glazing area reduces heat loss in winter and overheating in summer, while tall windows providing upward and downward views enhance daylight penetration and occupant connection to outdoors (Santamouris, 2015). This strategy addresses thermal comfort and visual comfort simultaneously, essential in temperate climates with variable weather (Boyce, 2014). Differentiating window shapes to protect glazing from weather extremes also reduces maintenance and risk of damage, contributing to building resilience (Kibert, 2016). The design limits snow and ice accumulation on façades, a key consideration in temperate climates with winter precipitation (Lehmann, 2010).

Passive Design with Active Support

Operating the building in a passive mode during winter—with minimal electrical heating to maintain comfort levels—follows principles of passive solar and envelope design, reducing operational energy demands (Lechner, 2015). Electrical heating is used sparingly, supplementing passive gains and conserving energy. This approach leverages thermal mass and superinsulation to stabilize indoor temperatures (Gustavsson et al., 2006). The use of heat exchangers and air recirculation is critical to maintain indoor air quality while retaining thermal energy, reducing heating loads and energy waste (Feist and Peper, 2016). This is especially important given the increased ventilation rates necessitated by the work-related activities inside dwellings, which generate higher internal heat loads and pollutant levels (CIBSE, 2015).

Integrated Daylight and Energy Management

The grouping of units around a common energy supply and environmental control system supports centralized management and maintenance efficiency, improving overall system performance (Kibert, 2016). The spatial arrangement enhances shared daylight access, reducing reliance on artificial lighting and improving occupant well-being (Boyce, 2014). Balconies, winter gardens, and downward-facing inclined glazing serve dual functions: they provide solar protection and daylight access, mitigating overheating while maximizing diffuse daylight (Santamouris, 2015). Cantilevered living spaces create microclimates with sheltered outdoor areas, extending usable living space while reducing heat loss (Gehl, 2010).

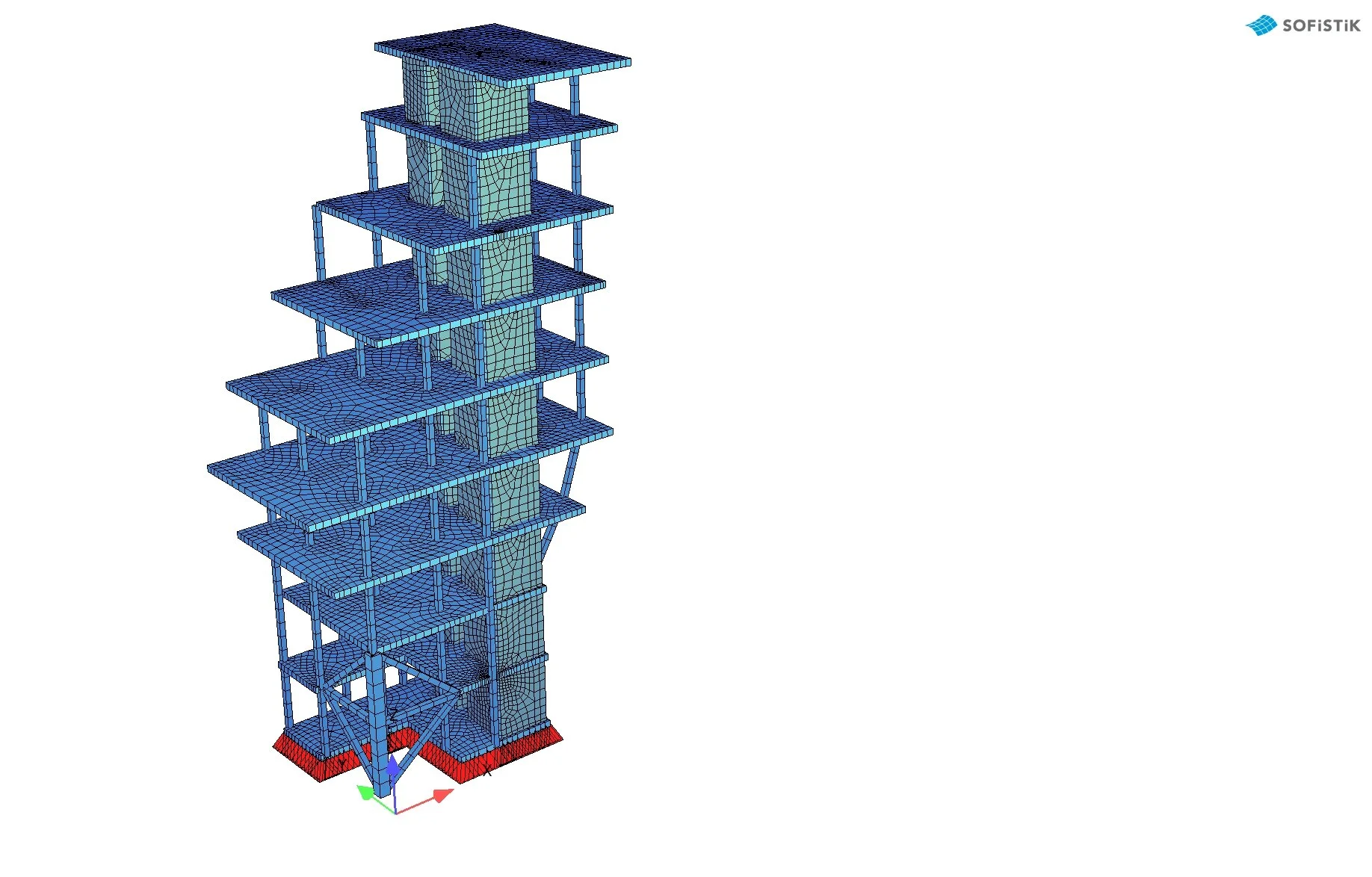

Modular Construction and Adaptability

The use of modular, prefabricated elements that can be assembled in rectilinear and triangular forms offers design flexibility and rapid construction while enabling customized spatial arrangements to meet occupant needs (Kieran and Timberlake, 2004). Modular construction facilitates quality control, reduces waste, and allows for disassembly or reconfiguration, supporting sustainability and adaptability (Lehmann, 2010). The ability to invert or rotate modules reflects an understanding of occupant autonomy and varied climatic response, enabling optimization of daylight, ventilation, and solar gain depending on site conditions and orientation (Lechner, 2015). This flexibility supports resilience for occupants in remote or seasonal settings.

Environmental Comfort for Remote and Variable Occupancy

The design strategy addresses the needs of remote occupants with varying occupation periods by providing independence through modular units with separate environmental controls. This allows systems to adjust automatically based on occupancy, minimizing energy use during vacancies and maintaining comfort during occupation (ASHRAE, 2019). This approach aligns with adaptive comfort theory, recognizing occupant variability and the dynamic nature of building use in temperate climates (De Dear and Brager, 1998).

References

ASHRAE (2019) ASHRAE Handbook—HVAC Applications. Atlanta, GA: ASHRAE.

Boyce, P.R. (2014) Human Factors in Lighting. 3rd ed. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press.

CIBSE (2015) Guide A: Environmental Design. 7th ed. London: Chartered Institution of Building Services Engineers.

De Dear, R. and Brager, G.S. (1998) ‘Developing an Adaptive Model of Thermal Comfort and Preference,’ ASHRAE Transactions, 104(1), pp. 145-167.

Feist, W. and Peper, S. (2016) Passive House Planning Package (PHPP) – User Manual. Darmstadt: Passive House Institute.

Gehl, J. (2010) Cities for People. Washington, DC: Island Press.

Gustavsson, L., Joelsson, A. and Sathre, R. (2006) ‘Life Cycle Primary Energy Use and Carbon Emission of an Office Building,’ Energy and Buildings, 39(2), pp. 154-162.

Kieran, S. and Timberlake, J. (2004) Refabricating Architecture: How Manufacturing Methodologies are Poised to Transform Building Construction. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Kibert, C.J. (2016) Sustainable Construction: Green Building Design and Delivery. 4th ed. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Lechner, N. (2015) Heating, Cooling, Lighting: Sustainable Design Methods for Architects. 4th ed. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Lehmann, S. (2010) Low Carbon Cities: Transforming Urban Systems. London: Earthscan.

Santamouris, M. (2015) ‘Regulating the Damaging Urban Heat Island Effect—A Sustainable Development Approach,’ Sustainability, 7(7), pp. 889-898.