Grand Egyptian Museum, Giza, Egypt

Further information and case study for this project can be found at the De Gruyter Birkhäuser Modern Construction Online database

The following architectural theory-based case study is not available at Modern Construction Online

Façade design of the Grand Egyptian Museum (GEM), Cairo: heritage, technology and environmental performance

The Grand Egyptian Museum (GEM), located at the foot of Cairo’s Giza Plateau, is a monumental cultural institution that seeks to articulate Egypt’s ancient heritage through a contemporary architectural language. The façade engineering was provided by Newtecnic, with architectural design led by Heneghan Peng Architects. This case study focuses specifically on the façade technology and its heritage significance, rather than the overall architecture of the museum. The GEM façade represents a sophisticated synthesis of High Modernist principles, regional identity and environmental responsiveness. Drawing on the lessons of the 1960s and 70s — an era that emphasised monumentality, climatic adaptation and symbolic clarity in civic architecture (Banham, 2015) — the design expresses sculptural massing and detailed tectonics that respond both culturally and environmentally to the desert context. As Watts (2019) notes in Modern Construction Envelopes, the development of façade technology during this period was often driven by the need to balance aesthetic monumentality with technical performance, a principle clearly evident in the GEM’s design. The façade system developed for this project served as a conceptual and technical precedent for the system implemented in Project 07, featured in the second edition of Modern Construction Case Studies.

Facade concept

The façade is conceived as a monumental envelope of sandstone planes, whose geometric rigor echoes the permanence of the nearby pyramids. Rhythmic recesses and subtle patterns inspired by hieroglyphic motifs create an interplay of light and shadow that varies over the course of the day. This formal austerity recalls Brutalist modernism but is firmly grounded in contextual modernism, where architectural language emerges from the site’s environment and heritage rather than imported stylistic norms (Edwards, 2011). Locally quarried sandstone was selected for its durability, thermal mass and visual continuity with the Egyptian landscape. The stone surfaces are textured with subtle hieroglyphic abstractions, transforming the façade into a narrative device that symbolises Egypt’s cultural identity and history.

Environmental and technical strategies

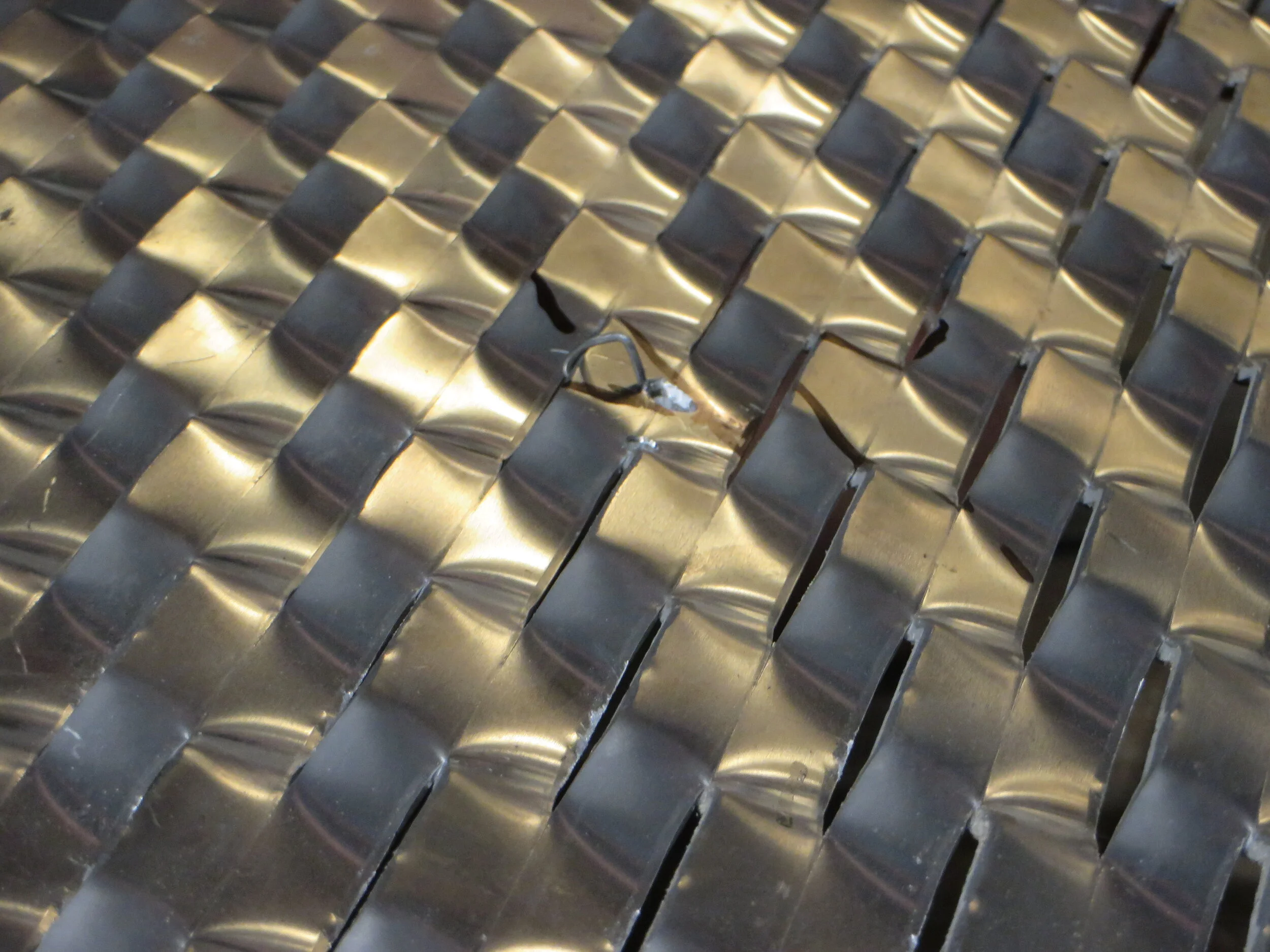

The environmental strategies of the GEM façade integrate passive design principles essential to sustainable construction in harsh climates, as discussed extensively by Watts (2023) in Modern Construction Handbook. The massive sandstone cladding acts as thermal mass, moderating internal temperatures by buffering heat gains from the intense desert sun. Small, strategically placed apertures reduce direct solar penetration, limiting overheating within the museum galleries. These apertures are deeply recessed and complemented by integrated brise-soleil inspired by traditional mashrabiya screens. This latticework filters daylight to reduce glare while preserving visual connection and privacy. Such passive solar control techniques maintain a high quality of interior daylight without compromising the protection of sensitive artefacts from UV radiation (Silver, 2013).

Moreover, the sandstone panels are mounted on a ventilated rainscreen system that promotes airflow behind the cladding. This assembly improves insulation, controls moisture ingress and enhances durability in Cairo’s extreme climate. This approach exemplifies the advanced rainscreen technologies and integration of environmental controls discussed in Watts (2016) Modern Construction Case Studies, demonstrating the role of detailed façade engineering in balancing aesthetic and functional requirements.

High Modernist influences on GEM façade design

The GEM façade draws inspiration from a lineage of High Modernist buildings that combined climatic performance, monumental form and cultural symbolism. Louis Kahn’s National Assembly in Dhaka is renowned for its sculptural stone envelope and deeply recessed openings, strategies echoed in GEM’s façade design. Marcel Breuer’s Whitney Museum, with its Brutalist stone cladding and institutional monumentality, similarly informs GEM’s material expression. Basil Spence’s British Embassy in Rome, noted for its lattice façades and sun shading devices, offers precedents for GEM’s use of mashrabiya-inspired solar control. Rifat Chadirji’s Ministry of Planning in Baghdad is another important influence, particularly in the integration of vernacular forms and symbolic patterning. Furthermore, the sculptural civic forms and use of light as narrative in Oscar Niemeyer’s Brasília projects resonate in GEM’s monumental and symbolic design. Finally, the Smithsons’ honest Brutalist textures and passive environmental strategies provide a material and tectonic precedent that GEM clearly reflects.

The façade exemplifies key High Modernist principles including monumentality through massing, climate-responsive design, material authenticity, symbolic form and pattern, minimalism, and contextual integration. These ideas align closely with the thematic frameworks outlined in Watts, A.’s Modern Construction Envelopes (2014), which stresses the importance of tectonic clarity and environmental integration in façade design.

Integration of façade and structure

Structurally, the sandstone cladding is fixed to a secondary steel substructure anchored to a reinforced concrete frame, enabling large, column-free gallery spaces within. Thermal breaks and flexible anchors accommodate differential thermal expansion between stone and concrete. The use of Building Information Modeling (BIM) was essential for precise panel alignment and coordination of mechanical and electrical services within façade cavities, reflecting the digital integration methods that Watts (2016) highlights in Modern Construction Case Studies as critical to contemporary façade engineering.

Conclusion

The Grand Egyptian Museum façade exemplifies a contemporary reinterpretation of High Modernist ideals adapted for the 21st-century Global South context. By combining symbolic form, passive environmental strategies and authentic materials, the façade operates simultaneously as a climatic buffer and a cultural artefact. It protects priceless antiquities while narrating Egypt’s heritage through its monumental stone skin. This project highlights how façade engineering can be rooted in history and place without sacrificing modern performance or sustainability.

References

Banham, R. (2015) The architecture of the well-tempered environment. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Edwards, B. (2011) Sustainable architecture: European directives and building design. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.

Heneghan Peng Architects (2020) Grand Egyptian Museum: project documentation. Dublin: Heneghan Peng.

Silver, S. (2013) Facade engineering. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.

Watts, A. (2016). Modern Construction Case Studies. 1st ed. Basel: Birkhäuser.

Watts, A. (2019). Modern Construction Envelopes. 3rd ed. Basel: Birkhäuser.

Watts, A. (2023). Modern Construction Handbook. 6th ed. Basel: Birkhäuser.